It was well before dark when Eleanor Su’s shift ended at Lovin Manor. That June night she cleared the dinner dishes at the elder-care home before telling a co-worker she needed to shower: She was going out. The other caregiver was too busy tucking residents in bed to wave goodbye. She didn’t notice a vehicle out front, didn’t watch Eleanor climb inside. She didn’t see taillights disappear down the dirt driveway into the north Scottsdale desert.

Eleanor Su never came back.

Four years later, 30 miles away, police would find another woman lying motionless on the concrete floor of a Tempe townhouse garage, a pool of blood beneath her head.

Only then would investigators begin to unravel the mystery of Eleanor Su’s disappearance.

Eleanor Su

In 2005, Eleanor Su left the Philippines after a falling out with her husband. She told her young children she was going away, her brother recalled, but that when she made it, she’d come back for them.

She came to the United States on a tourist visa and worked in a New Jersey restaurant before making her way to Arizona to be near her big brother, Peter Pigon.

“She only thinks that America is full of opportunities,” Peter recalled. “... That’s why she said: ‘Give me five years. I’ll make it.’”

Peter believed her. She had already done it back home.

The fifth of 11 children, Eleanor married her sophomore year of college and quit school. But she had an entrepreneurial spirit. She and her husband ran a small food stand outside their home, started a sewing business and eventually built a lucrative glass and aluminum company, Peter said.

Eleanor wasn’t like traditional Filipino women, her brother explained, quiet and demure. She was open, outgoing and liked to meet new people despite a childhood injury that forced her to wear dentures around age 12.

Her forward nature was all the more reason Peter warned her to be careful. When she went missing, he recounted for detectives the words he’d once told her.

“... (Y)ou think of America like a beautiful country,” he had said. “Everybody’s good. ... (But) it’s like the Philippines. There are good guys. There are bad guys. … Just be careful.”

In late spring 2006, Eleanor, 39, interviewed for a job at a care home called Lovin Manor in far north Scottsdale. Owner Martha “Marty” Ziomek thought it strange that Eleanor’s boyfriend, Wade Bradford, stayed for the interview and had to approve the hours she could work. Bradford unnerved Marty.

A few weeks after Eleanor started work, she confided in her boss that Wade was possessive and jealous, that she was afraid of him, Marty later told detectives. But Eleanor never said why.

Marty thought the young woman was a hard worker and knew she needed a place to stay so she recommended her to a friend who needed a part-time, live-in caregiver.

Eleanor would work three days at Lovin Manor, three days for Marty’s friend.

She took a suitcase to her new room in the house about a mile from the care home.

On June 11, Eleanor left Lovin Manor for her night out. She was supposed to start work at the other home June 13.

But she never showed.

Eleanor had always been reliable employee. Maybe she misunderstood because of the language barrier and thought she was supposed to start the following week, Marty thought. Marty decided to wait until Eleanor’s next shift before she got too worried.

When Eleanor didn’t report to work there June 16, Marty became anxious. Eleanor’s voice mail was full. Marty knew she lived paycheck to paycheck, and that day was payday. Why hadn’t she come in? She called Eleanor’s brother. He hadn’t heard from her either.

It was time to call police.

Detectives searched Eleanor’s room at the home about a mile from Lovin Manor. They found four shirts and a pair of blue pants hanging in her closet. In a small red suitcase they found an English dictionary and her Filipino driver’s license. There were several business cards. Handwritten on the back of one were numbers for checking and saving accounts and the name and address for Wade Bradford in Fountain Hills.

But police couldn’t find Wade at that address, or anyone else. They visited several times over the next two weeks, but no one was home. Another Phoenix address for him was out of date. A third was a post-office box.

Detectives interviewed one friend who said Eleanor was afraid of “that man” — Wade Bradford. He wanted to marry her and take her to California, possibly Los Angeles, but she didn’t want to go. Another said Eleanor wanted to “take off” so no one would ever find her.

Yet nothing pointed to where Eleanor might be.

Bank of America later told police she had three accounts, but there was no activity on any of them. One was overdrawn, a second had a balance of $2.52. The third held just 26 cents.

Police tracked Eleanor’s phone through cell tower hits from north Scottsdale near Lovin Manor to Mesa on June 11. Phone records showed detectives the last outgoing call was at 5:32 p.m. on June 12. That call hit off a cell tower near Center Street and Broadway Road.

At 7:20 that same night near Alma School Road and Southern Avenue, Eleanor’s cellphone registered a final ping.

Wade Bradford

ade Bradford was born in 1960 in California. He went to Mission San Jose High School in Fremont, southeast of San Francisco, where he was on the track team and played varsity football.

Wade would later tell a judge he had a bachelor’s degree in engineering.

His father, Eugene Bradford, said Wade worked for Hewlett-Packard upgrading older computers, and had a nice home.

Wade Bradford

But he went independent, his dad said, because he wanted to make his own hours. He was married and had three children but later got divorced.

Records of Wade’s activities in Arizona are sparse.

Years after Eleanor’s disappearance, he would tell police that he was self-employed in “adult entertainment.” He handled the advertising for women who sold “sensual body rubs.”

The month after Eleanor went missing, in mid-July 2006, Wade called a Scottsdale detective.

He said he had heard from a family member that police were looking for him. He asked if Eleanor had been found. He was “freaked out” about the whole thing, he said.

Wade told the detective that Eleanor had a history of getting upset, not wanting to talk to people, though he thought she would have shown up by then.

Eleanor was in the country illegally and was trying to find a sponsor, he told the detective. Wade said he had dropped her off maybe June 12, at the corner of University and Country Club in Mesa. Eleanor told him she was going to a restaurant to meet someone who was going to sponsor her, possibly a home-care worker, he said.

Wade had left town for California after that, he said — and hadn’t talked to her since.

He didn’t know if Eleanor was “missing in a bad way” or was missing “under a new identity,” he told the detective.

How, the detective asked, would Eleanor have been able to leave under a new identity? Wade said a store where Eleanor sent money to the Philippines could create a new identity for her and that several of her friends were going home.

After talking to the detective on the phone, Wade sent him a long e-mail outlining his relationship with Eleanor but said he wouldn’t come in to the station. He was behind on child support and taxes, he said, and was afraid he’d be arrested. He repeated that he didn’t know where Eleanor had gone.

Her brother told police about his own phone call with Wade Bradford.

“So I told him, ‘What happened to Eleanor?’” Peter recalled in an interview. “He said, ‘I don’t know. I was with her, but at midnight she wants me to drop her … in Mesa.’”

Peter was incredulous.

“Would you drop her at midnight, I said, a very unholy hour? Would you drop her on the corner?”

Wade told him not to tell anybody and hung up, Peter later told police. Peter said he called back six times, but Wade never answered.

One of Eleanor’s friends said Eleanor was angry at Wade because he wouldn’t give her money and angry at Peter because he always tried to tell her what to do.

A Scottsdale detective was suspicious of the disappearance. But when he explained the case to Peter, he said her friends indicated she might have been planning for a long time to disappear.

Family members back home thought maybe she’d just left without telling anyone.

In a phone call to the Philippines, Peter reassured his mother.

“I said, ‘Don’t worry. We’ll find her,’” he recalled. “… You will see her again, I said. We’ll try our best to find her. But America is a big place, I said. You cannot just go around in one day.”

Even then, he didn’t believe his own words.

“I said no,” he recalled thinking. “... I feel it. I feel she is lost.”

Missing persons report from the Scottsdale Police Department issued for Eleanor Pigon Su in June 2006.

By the end of July 2006, the month after Eleanor last showed up at work, police had exhausted every lead. A detective put his case notes in a binder labeled Eleanor Su—06-15511 and placed it on one of the bookshelves that line the cold-case room. Hers joined a couple of dozen others that remained unsolved.

There was no body, no real evidence of a crime.

Eleanor Su was just gone.

IN 2009, WADE BRADFORD MET NATALIE ALLAN. He would later tell police she had an interview with him, though he wasn’t specific about the kind of work they did.

The pair had an on-again, off-again relationship. He was older and charismatic, a braggart, her mother, Brenda Allan, later told police. It seemed he could talk her into anything.

Natalie was bipolar and struggled with drugs as early as high school in Fountain Hills, Brenda told police. She described a young woman with an adventurous streak. Natalie had eloped with a boyfriend before she turned 21.

Brenda would tell police the story.

“… (The guy) drove all the way to Arkansas where she was going to a private school,” she said. “… (T)hey went to Las Vegas and got married. She was just 20. … And (he) was 19. So, how much was adventure? How much was love? It was hard to say.”

The two had a son, but Brenda said: “They didn’t last.”

An aspiring writer, Natalie tried several colleges — studying English and journalism — but nothing stuck. When she needed money, she worked as a waitress or a caregiver in group homes for the disabled.

Natalie Allan

But Brenda Allan also knew about other jobs her daughter sometimes took.

“I’m going to venture to say it was more her lifestyle, the prostitution and the dancing that she did,” her mother told police, describing emotional late-night phone calls with her daughter. “We’re a pretty strong, Christian family, but we’re not judgmental. I told Natalie over and over: ‘I accept you. I love you. I don’t like your actions.’ So she learned to trust that at least.”

Wade Bradford later described Natalie to police as an adult entertainer.

In 2010, when she was 27, Natalie met a new man, Kevin Myles. They started dating, and a couple months later she moved in with him. Yet Natalie was indecisive. She moved out several times. She confessed to Kevin she was falling in love with him but wanted to make sure she didn’t still have feelings for Wade. In late May that year, she packed and left again.

She sent Kevin a text message, he would later tell police, saying she was on a road trip with Wade. First they were in California. A few days later, they were headed to Seattle. But soon, she called Kevin and said she loved him. She wanted to come home. He booked her on two different flights, but she missed both.

By the time Natalie got back to Arizona, she’d decided to be with Wade. She talked about moving to Portland. But she wanted to see Kevin to say goodbye. He met her at a Circle K on Baseline Road around 1 a.m., drove for a while and parked so they could talk.

“She’s teary-eyed and sad and tells me she loves me and wants to be with me,” Kevin later told police. “So … we go to my house. … She’s really happy, and she tells me … she can love me now because … she needed to do that trip to find out.

“… And she doesn’t wanna be with him no matter what, and she’s gonna stop talking to him. … We want to try to build a life together.”

She had made her decision. But her things were still stored in the garage at the Tempe townhouse Wade rented. Her clothes. Her birth certificate. The maroon Bible embossed with her name.

“So she’s pretty happy all day (the next day) and she’s like, ‘Well, you know, let’s go get my things,’” Kevin later told police.

Around 9 p.m. on May 29, Kevin and Natalie pulled up to the Tempe townhouse Wade rented and knocked on the door. Nobody answered.

As they stood on the sidewalk under the glow of a street lamp, Natalie called Wade and told him to hurry up. Wade emerged from between the two rows of townhouses and walked up the front-porch steps to his unit.

“Garage,” he said, as Kevin would later recall.

Kevin and Natalie headed to the alley and waited for the automatic door to open.

Crime scene photo of 702 S. Beck in Tempe, the night of May 29, 2010, when Natalie Allan was found shot in the head. (Tempe Police Department)

inutes later, Kevin dialed 911. “Uh, I just — I need to report a murder,” he said in a clear voice, but panting. “702 Beck.”

What’s happened?

“He just shot her in the back of the head. She’s dead.”

As sirens blared in the neighborhood, Kevin flagged down an approaching patrol car.

“She’s dead,” he told the arriving officer. “He f--king shot her in the back of the head.”

Kevin folded his arms as he recounted again what he saw to police. Transcripts of their conversation lay out the details:

“He opens the garage. She walks in and starts sorting stuff. He walks up and just shoots her in the back of the head.”

Wade was in jeans, Kevin told the police. Maybe a plaid flannel shirt? Heavy guy. Acne scars. ... The gun was almost touching her head. She dropped.

“… (T)he second he was done … he turned around … so I dropped that suitcase and I … tripped over the curb and landed in the bush face first. .. And I’m waiting to feel what a bullet feels like ripping through you. … Hoping he’s not a very good aim.

“He just stopped … and then he said, uh, ... ‘Stay down.’ … When he said that I looked up again. I mean he just ran that away. Not a very fast runner.”

Where was the gun, the officers asked.

“He had it in his hand. As long as I watched him he had it in his hand. … I’m standing there watching him run down the alley. … and I duck back behind a wall and just, ‘What the hell am I doing, you know?’”

He went in to see her, he said, and knew: “I mean, I knew the second he did it there was no chance she was …”

The next morning, Wade’s picture flashed on the television screen during a news broadcast. Police were looking for a man in connection with a shooting on South Beck Avenue in Tempe. They considered him armed and dangerous.

A manager at Oregano’s on University Drive called police the next night. He didn’t know the man’s name, he said, but recognized him on the news as one of his regulars. Now, the man was sitting at the bar.

The manager walked past Wade one more time to make sure it was him. They chatted about Suns basketball and the hockey playoffs.

Then police arrived and put Wade in handcuffs.

At the Tempe police station, Wade asked for a cup of coffee. He’d had a couple of beers and felt groggy, he said. He was trying to wake up. A detective read him his rights and asked what happened at 702 S. Beck. Transcripts of their interviews record the rest.

“What happened the other night is, um, (Natalie) came to pick up her stuff with — with, um, Kevin. And it got really complicated. Because Kevin’s been wanting to kill me,” Wade said. “... He said that.”

Wade told the detective his vacation with Natalie had been nothing more than a trip with a friend. He didn’t care she was going back to Kevin. He was used to her bouncing back and forth between men.

Kevin, on the other hand, had been threatening him, he said.

He’d spent the past two days in Papago Park, trying to “reverse engineer” what happened. He had expected things to go smoothly that night, he said. But he had taken a loaded gun from his car with him to the garage, just in case. He didn’t want to get beaten up, didn’t want to be defenseless. “I’m not a boxer or a fighter,” he explained.

Wade told police he’d met the pair, then gone into the garage.

“... (A)ll of a sudden he started coming at me and I pulled my handgun and he was charging me. I was, you know, threatened for my life. So I turned around and I think I fired a shot or something and then I chased him and he dropped down in the ivy.

“So I wasn’t sure how bad I hurt him, you know, what — what the deal was. So at that point I think I panicked and left. I just like that. Happened really quick.”

Weapon recovered during investigation of the shooting death of Natalie Allan at 702 S. Beck in Tempe. (Tempe Police Department)

Wade told detectives again and again it was self-defense, that Kevin charged him, and he fired. The last time he remembered seeing Natalie was on the street before he opened the garage door. He never saw her in the garage, he told police.

“Well unfortunately we all know that (Natalie’s) the one that got shot. Right?” the detective said, according to the transcript.

“No,” Wade answered. “Na — (Natalie) didn’t get shot. Nat — this wasn’t Nat — this was Kevin.”

“How about (Natalie)?” the detective asked.

“(Natalie) didn’t get shot.”

“(Natalie) got shot,” the detective said. “Okay.”

If Natalie was shot, Wade wanted to know, how was she? Was she all right?

“(Natalie) did not make it,” the detective said. “You ran — you ran past her three times.”

“I did not,” Wade said. “I swear I did not. I swear to God I did not see her. I — I saw him coming, I fired. … I did not see her.”

By the end of the interview it was clear police weren’t buying his story.

“... I’m tired of listening to the lies,” the detective said. “I mean you had an opportunity to tell us the truth.”

Maricopa County grand jury indicted Wade Bradford on a first-degree murder charge in the death of Natalie Allan on June 8, 2010. The judge set a $750,000 bond. Wade sat in a Fourth Avenue Jail cell waiting for trial.

In the weeks and months that followed, police continued to interview witnesses.

A woman named Morgan Mankis had been upstairs at the Beck townhouse the night of the shooting.

She told police that Wade, also known as “Red,” ran a personal escort and private, independent adult-entertainers business — including “lap dancing, massage and full-service girls,” as an officer described it in the report.

She told police she had seen Natalie arrive with a man at the townhouse that night. She then saw Wade inside, she said. But she insisted she hadn’t witnessed the shooting, and hadn’t heard a gunshot.

Dwayne Bearup, one of Natalie’s old boyfriends, described Wade as having a “Hitler-level charisma” and said he could “make people do things.”

Kevin Myles repeated to police a story Natalie told him over and over when they first met.

Natalie visited psychics and talked about past lives. She was exploring her spirituality. She told Kevin that she and Wade had a connection in a past life.

“She believed,” Kevin told them, “that he had murdered her in that past life.”

Photo of storage locker B-32 at Westview Self Storage in Goodyear. (Goodyear Police Department)

est of Phoenix, where Goodyear suburbs begin to turn to desert, the sandy concrete walls of the Phoenix Trotting Park loom over the freeway, decades removed from their horse-racing past.

Beyond the empty racetrack, south over a bridge across the canal, rows of former stables now house storage units, padlocks dangling from their doors.

On a February afternoon in 2011, George Fleureton, who’d been working at Westview Self Storage for about two weeks, was helping manager Richard Sindelar clean out B32.

The Goodyear storage facility had been hounding the renter of B32 for months.

He hadn’t made a payment since April 22, 2010. The manger sent a late notice May 24. Auction notices were mailed out Oct. 8, Oct. 15, Dec. 13 and Dec. 20.

Finally, in January, Richard had cut the lock off the door. He hadn’t seen anything worth auctioning so he locked it back up. They had to wait for a dumpster to haul everything off.

Richard had never seen the renter at the storage facility. He’d only seen his driver’s license picture attached to the rental agreement. The man usually paid by credit card over the phone.

But since April, no payment had ever come through. Now it was February, and they were finally getting around to cleaning the place out.

They swung open the door.

A fine layer of dirt had swept in and covered the concrete floor. Richard unzipped a suitcase inside, and found old clothes and a shoe. Plastic bottles of bleach, a black garbage bag and a box of baking soda lay about. On the right side, close to the door, sat a trash can wrapped in plastic. Richard ran his hand alongside it. It felt like tires. But as he sliced through the plastic, a rancid smell hit their noses. The more he cut, the worse it smelled.

Better call police, he told George.

When a Goodyear officer arrived, she noticed a clear gallon jug with a white, crystallized substance on top and then the smell. They were going to need a hazmat team.

Photo of storage locker B-32 at Westview Self Storage in Goodyear. (Goodyear Police Department)

Less than an hour later, officers in white and yellow hazmat suits unwrapped multiple layers of plastic and cloth from the gray, Rubbermaid trash bin. Duct tape and plastic zip ties held the layers together. With a sterile glass pipette, they took a sample. There were no hazardous materials.

Officers peered in.

What they saw looked like a spine and rib cage still covered in skin submerged in dark fluid. The figure was curled in a fetal position at the bottom of the trash can.

An officer asked Richard if he’d ever smelled anything like the stench coming from B32.

“When I was in the Coast Guard back in the ’60s we had to fish out dead bodies,” he said. “And I thought it kind of smelled like that but not quite.”

Police asked to see the rental agreement. At the bottom of the page was a signature:

Wade Bradford.

He’d rented the unit June 13, 2006.

A quick call to dispatch told police where he was and why he’d stopped paying his bills. For the past eight months, he had been sitting in the Fourth Avenue Jail, charged with murder.

The trash can and all of its contents were taken to the Medical Examiner’s Office, where the remains were determined to be those of a petite, light-skinned woman, possibly aged 33 to 58.

She had no scars or tattoos, no clothes. Her only belongings: a small bead, a hair extension on a clip and, in her left earlobe, a single, white metal earring of a seated cat. She had brown hair and wore dentures with no serial number. There was also evidence of a healed gunshot wound to her face from many years ago.

The Goodyear Police Department Hazmat Team prepares to remove a body from a storage locker at Westview Self Storage in Goodyear on June 11, 2006. (Goodyear Police Department)

It was hard to tell how long she’d been dead, but the manner of death was homicidal violence. The medical examiner’s report was clinical: blunt force trauma to the torso with possible obstructive asphyxia.

The examiner found evidence of bleeding into the chest and abdominal cavities and jagged tears in the liver consistent with a “blunt impact injury.” Plastic bags wrapped in clear packing tape covered her head and neck, blocking her nose and mouth.

In Goodyear, detectives cataloged items in the storage unit: packing tape, zip ties, a can of Lysol, an empty bottle of bleach, bug spray, and Arm & Hammer baking soda boxes.

List of evidence recovered by the Goodyear Police Department from Westview Self Storage.

Video surveillance at the storage facility hadn’t worked in years, and even if it had, the manager said, it would have only kept recordings for 14 days.

But every renter creates an entry and exit code, and the storage facility had kept a log.

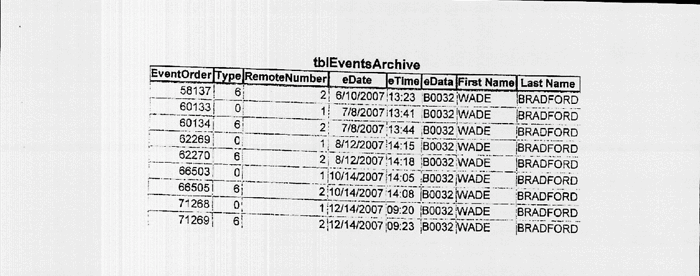

It showed Wade Bradford keying in almost every month until the end of 2007. He — or someone who knew his key code — went in for 11 minutes on June 26, 2006. For six minutes on Aug. 12, 2006. Four minutes, May 13, 2007. Three minutes, Oct. 14, 2007. And finally, three minutes, Dec. 14, 2007.

Electronic log of access to storage unit B32 by someone using Wade Bradford's access code. Under the RemoteNumber column, "1" indicates logging in, "2" indicates logging out.

Police still didn’t know whose body they had found.

An e-mail from the Phoenix Police Department about the recovery of remains in Goodyear circulated among local law-enforcement agencies. It asked officers to check missing-persons databases to see if any matched this description: a female subject, 5 feet 2 inches, Caucasian or Hispanic, no tattoos, brown hair. Estimated to be around 40 years old and 120 pounds. She had a deep scar on her chin, partial dentures with no serial number and metal in her jaw from an old, low-impact gunshot wound unrelated to her death.

In Scottsdale, a detective read the e-mail and thought there was a chance this could be his cold case from 2006. In the years since Eleanor Su’s disappearance, he had periodically checked to see if she had ever resurfaced. She never had.

He went to see Peter Pigon again to ask if he’d ever heard from Eleanor. No, Peter said.

What about dental work? Had Eleanor ever had any? Yes, Peter explained. When Eleanor was young, their father got into an argument with a neighbor, who shot at him. Eleanor was hit in the face. She’d worn false teeth ever since.

The detective took a sample of Peter’s DNA.

Weeks later, officers were back on his doorstep.

His sister, who’d been missing for so many years, had been found.

Peter hung his head.

“I knew it,” he told them. “Bradford killed her.”

n late June 2011, a Goodyear detective met Morgan Mankis at her home in Apache Junction. They sat in the kitchen as Morgan recounted how she met Wade a few years earlier.

She found him on Craigslist in reference to an escort service, she said. She worked for him and was at the Tempe townhouse the night Natalie Allan died.

But the detective wanted to know about Eleanor Su. Had Wade ever mentioned her name? No, Morgan said. But then she got quiet. She remembered seeing a picture of a petite Asian woman in a red dress. Had Wade ever talked about marrying a woman from the Philippines? Yes, he had, Morgan said.

Morgan followed the detective to his car. He took two pictures of Eleanor from a white notebook and handed them to her. One showed Eleanor on a couch in a bikini. The other was a headshot of her in a white shirt with jewelry on.

“Oh my God, that’s her,” Morgan said. “That’s her.”

She had been looking through some of Wade’s things once, she said, and found pictures of Eleanor. She asked who the woman was, and Wade said she was a girl who used to work for him.

Police records and interviews with those who knew Eleanor show no indication that she ever worked for Wade.

But Morgan remembered her face.

A Maricopa County grand jury indicted Wade Bradford on counts of kidnapping and first-degree murder in the death of Eleanor Su on Dec. 4, 2012.

In the following weeks and months, police dug deeper into the evidence.

The Department of Public Safety analyzed evidence taken from the storage unit. Its lab examined four fingerprints found there. Prints from a U-Haul mattress-bag package and a package of pool-shock chlorine matched Wade’s fingerprint records. Other prints were inconclusive. Additional prints were not compared because of insufficient detail for identification.

The lab also analyzed DNA taken from the scene. Its report said DNA found on two blue plastic caps contained a mixture of two people’s DNA. The “major contributor” was Wade Bradford. Samples taken from some other items also showed mixtures of at least two people’s DNA but could not be conclusively matched to Wade.

Police also wanted to know more about Wade’s relationship with the two women.

Photo of Natalie Allan presumably taken while on a trip with Wade Bradford. (Tempe Police Department)

In early 2013, Goodyear and Tempe police detectives interviewed Brenda Allan, Natalie’s mom. She talked about how Natalie and her brother were adopted, Natalie’s high-school years and brief marriage, her relationships during the last few years of her life.

But there was something Natalie said that stuck with her.

“I could tell towards the fall of ’09 that she was not trusting him (Wade), and that’s when she started sharing that — this is the part I can’t really remember clearly, whether or not she said ‘girl’ or ‘girls’ — were missing,” she told the detectives.

Brenda said she asked, but Natalie wouldn’t say more about the idea of a missing girl. She knew if she pushed she wouldn’t see her daughter.

“I got the impression that she was trying to protect us from the information,” she explained. “Natalie was a pretty strong girl ... She had some street smarts, obviously. For whatever reason she felt she could handle it.”

Brenda saw her daughter for the last time on Christmas Day 2009.

“She seemed more relaxed that Christmas Day because she had a plan,” Brenda told police. “She was leaving Wade. She was moving out. That’s when she moved in with Kevin in January. And that’s when she was saying more that she was afraid of Wade. And then she says he may have killed a girl.”

The two murder cases against Wade Bradford proceeded on parallel tracks, with procedural checks along the way.

In February, Bradford had two attorneys. Bruce Blumberg, representing him in the Natalie Allan case, told The Republic that his client was innocent until proven guilty, and would not comment on his defense strategy. A public defender, Jamie Jackson, represented Bradford in the Eleanor Su case. He declined to comment. When asked whether Wade Bradford would grant an interview, both attorneys said they would advise him not to talk to the press. Wade declined a formal request through the jail to be interviewed.

Wade Bradford talks to the judge during a pretrial hearing in Maricopa County Superior Court on April 19, 2013. (Pat Shannahan/The Republic)

In May, though he cautioned against the decision, a judge allowed Wade’s request to represent himself in both cases.

In a handwritten motion filed with the court, Wade wrote: “Defendant has 30 years experience managing projects of varing (sic) levels of complexity. Further, this defendant has close to 3 years legal exposure/observation with this case in addition to dozens of complex cases defendant has followed while detained at 4th Ave. jail. ... Only this defendant has the depth of knowledge encompasing (sic) both this three year old 2010 case and the volumous (sic) 2012 case. Defendant has a detailed strategy to manage this case to trial in a timely and comprehensive fashion.”

Through a spokesman, the County Attorney’s Office declined to comment on either case. Trial in the first one, Natalie Allan’s death, is scheduled to begin Sept. 23.

he three-year anniversary of Natalie Allan’s death has now passed. The Allans want justice, but they also have strong faith. Helping others with their grief through a church group has helped ease their own.

On a springtime evening, Natalie’s parents leaned against a heavy wooden table at a Tempe restaurant, a longtime family favorite, and tried to find the words for the past three years. They declined to talk about the upcoming trial and only spoke briefly about their daughter, not wanting to affect the outcome of the trial. They chose instead to talk about how their faith has sustained them.

“This gets back to Romans 12,” said Natalie’s father, Alan Allan. “Loving your enemy, right? We can’t put Wade into any other category than that category. And we’re asked to love him and forgive him. That’s what Romans 12 says.

Bible belonging to Natalie Allan that was near her when she died after a gunshot wound to the head at 702 S. Beck in Tempe. (Tempe Police Department)

“Romans 13 says, ‘I put all authority in place to deal with those who don’t want to follow the rules.’ … Even though God is in control … he also puts governmental authority in place to deal with the brokenness. … We can get justice in the world without generically saying that God will work it out.”

Until then, they remember their daughter. The toddler who loved to give hugs and kisses. The 9-year-old baptized by her father in the family’s backyard spa. The junior-high cellist who played in the Chandler Youth Symphony. The high-school student who lettered in track.

They also remember the aspiring writer. The young woman who was getting her life together. Shortly after she died, a certificate came in the mail that showed she’d passed the test to become a medical transcriptionist.

Natalie’s mother likes to visit her marker at Mariposa Gardens cemetery. In Spanish, mariposa means butterfly. “I miss her every day,” she said. It pleased Brenda to know that the Bible embossed in gold with Natalie’s name was near her when she died.

About once a month, her father listens to the last voice mail Natalie left to say she couldn’t make it to dinner. “Oh hi, Dad,” she begins.

“She was very interested in spiritual things,” her father recalled. “And, of course, I was always into Bible study. She would always throw out questions, and we would have dialogues about it. And that’s part of what I miss, just having a fun conversation or an e-mail interaction with her on her beliefs or the latest thing she’s running up against.”

Natalie’s name means God’s gift, her father said, and she was.

Eleanor Pigon Su (Courtesy of family)

Eleanor Su’s family hasn’t held a memorial service. Maybe next year, Peter said. In the Philippines. His sister’s ashes will be added to the family cemetery.

He remembers the sister who sent money and medicine home to their mother. The aunt who hugged his children like they were her own. The woman who wanted to build a new life for herself in America. He remembers the sharp dresser, the cook who made the best beef stew, Filipino style.

He sometimes thinks about the way she died.

When Eleanor was found, despite the condition of her remains, Peter asked the medical examiner if he could see her.

“They said she is unrecognizable anymore so you can’t do anything except wait for DNA,” he recalled. “I just had that feeling that I wanted to go and be near her even if she’s unrecognizable because of that feeling: she’s the one that was found.”

But he never went.

He knows the waiting to find Eleanor was difficult for his family. He remembers the phone call with his mother, his well-intentioned reassurances that she’d see her daughter again. But his own intuition had been right all along.

Eleanor Su’s mother died waiting for her to call.

For this story, Republic reporter Kristina Goetz reviewed more than 1,000 pages of court documents, reports and investigative files obtained under open-records requests with police agencies in Goodyear, Scottsdale and Tempe.

Those police files also included information from other agencies, including the Arizona Department of Public Safety, U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement and the Bureau of Immigration in the Republic of the Philippines.

To build the record of events, Goetz reviewed police-case narratives, incident and missing-person reports, audio recordings and transcripts of police interviews, a 911 call, crime-scene photos and evidence logs, Maricopa County medical-examiner reports and DPS scientific-examination reports.

She also interviewed friends and former employers of Eleanor Su as well as relatives of Su, Natalie Allan and Wade Bradford.

Originally published in the Arizona Republic