LIFE INSIDE A WAR ZONE

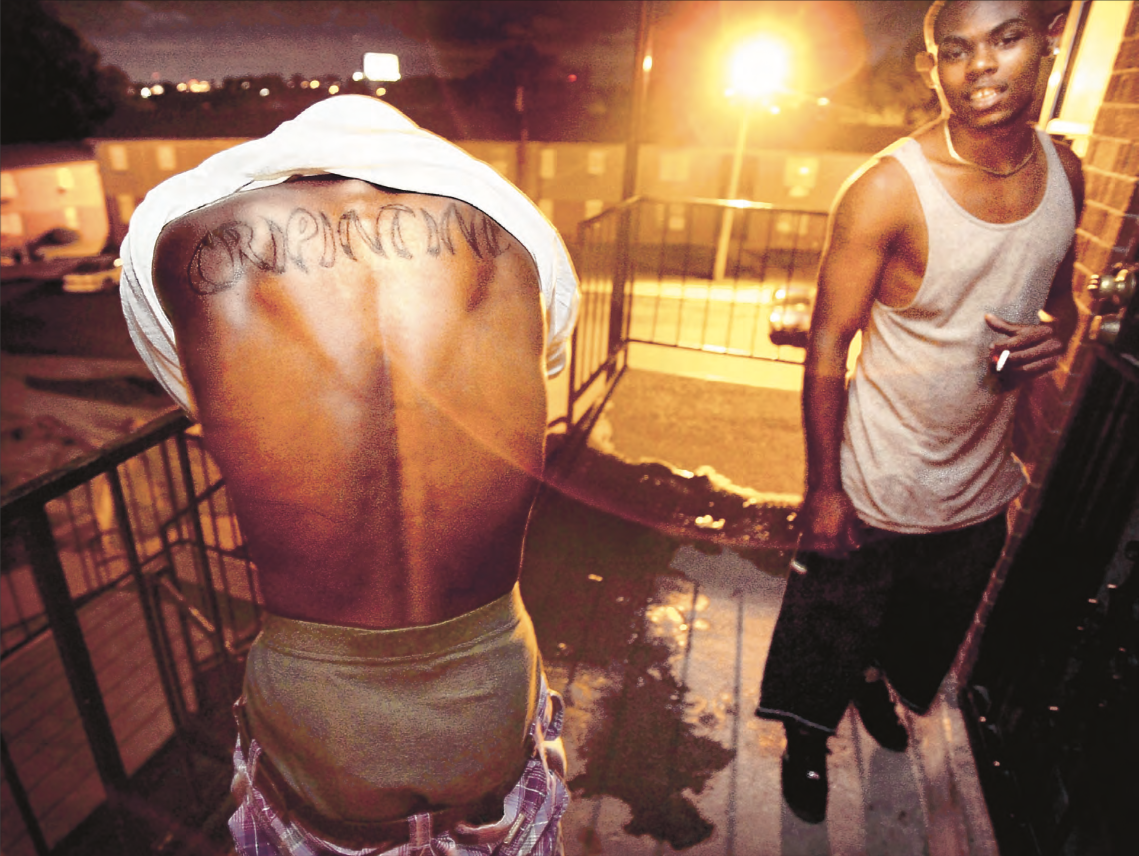

CLEMENTINE: A resident of the Warren Apartments shows off his “Cripintine” tattoo referring to the largest gang, the Kitchen Crips, in the 1300 block of Clementine. The short stretch of Clementine sand a few single-family homes on a stretch of Ferguson just north of there has recorded more incidents of violent crime in the past nine years than any other residential area in Memphis.

Across the city, more than 30,000 residents live in neighborhoods with the constant threat of violence

BULLETS SHATTER PEACE OF MIND: Bullets fired outside Qunettia Robinson’s unit at the Warren Apartments shattered a picture on the wall. That same August night, one of the bullets hit Robinson in the shoulder while she sat at her kitchen table. She was reaching for her infant son at the time, but he was not injured.

Shortly before bedtime, Qunettia Robinson heard neighbors arguing below her second-story apartment. She peeked out the front door and watched as a group of men gathered in a circle, a couple with guns tucked in their waistbands.

In her seven years as a tenant in the Warren Apartments, she’d seen people throw punches, drug dealers lurk in the shadows and cars drive down Clementine with bullet holes in the doors.

A decade of police reports bear the same witness: her South Memphis neighborhood records the most violent crimes year after year; a dubious distinction in a city beset by violence.

On average, a violent crime was reported in the neighborhood nearly every other day for almost a decade.

There have been five murders in the 1300 block of Clementine, alone, since 2006.

Qunettia kept from trouble, she said, by keeping to herself. So, on this August night, just before 10 p.m., she latched the front door, muffling the angry voices below.

Anthony Seay Jr., Qunettia’s boyfriend, played dominoes on the coffee table with her daughter, while she settled into her favorite kitchen chair.

She reached down to pick up her infant son when, suddenly, someone popped off several rounds outside.

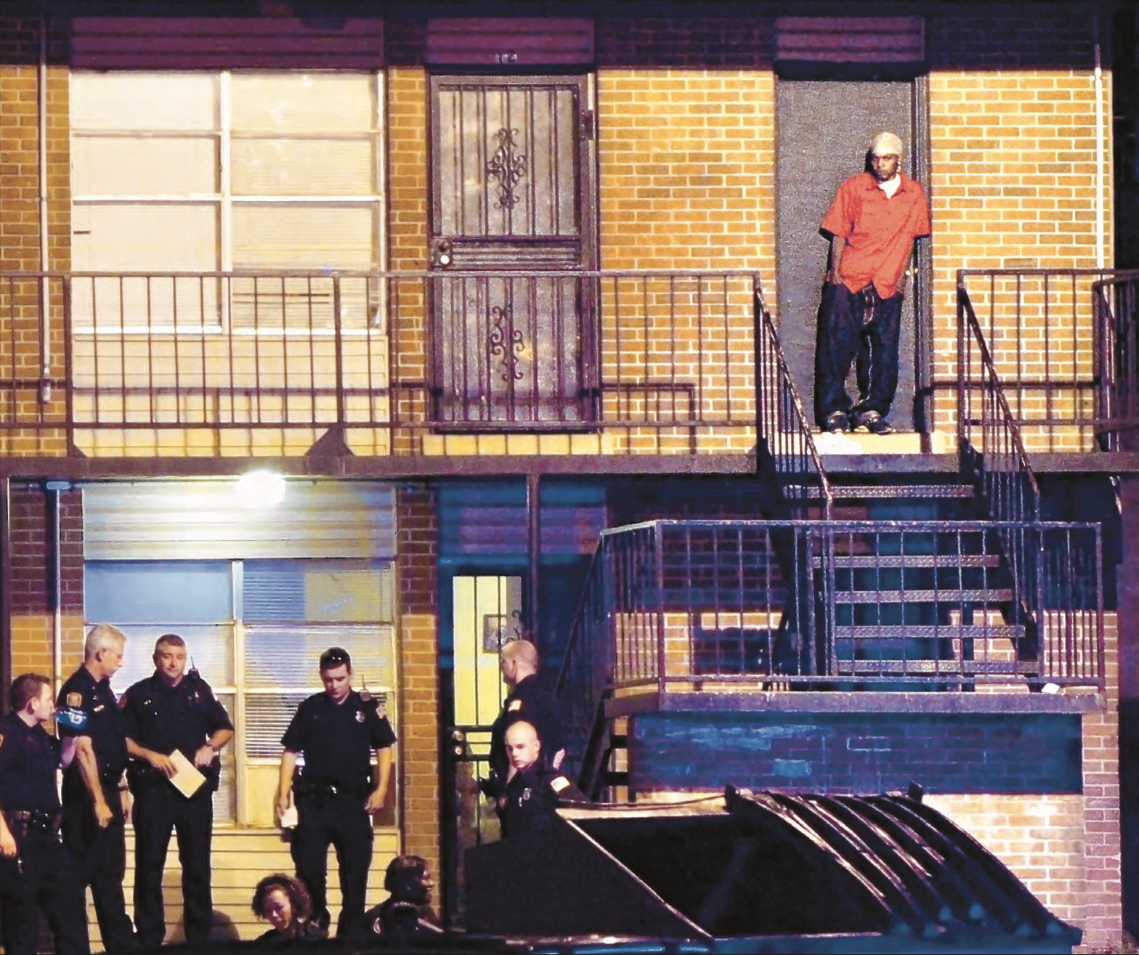

LATE-NIGHT CALL: Memphis police officers respond en masse to a late-night shooting call from the 1300 block of Clementine at the Warren Apartments. The violence turned out to be a domestic dispute over stolen baby boots. The 248-unit Warren Apartments on Clementine sit off Elvis Presley Boulevard, just north of I-240 and less than 2 miles from Graceland. “Clementine was a war zone when I was a rookie in 1990,” said Lt. L.D. Carson, who works in the Airways precinct. “Not much has changed.”

‘I THOUGHT, ‘I MUST BE FIXIN’ TO DIE’’

She heard a whizzing noise near her ear and hit the floor with a thud, landing on the infant.

The baby was screaming and crying, the weight of his mother smothering him. But she couldn’t move. Her body felt heavy, stuck.

Bullets from a gunfight below pierced the outer wall of the apartment and flew across the living room.

“Don’t move!” Anthony screamed. “You’ve been shot!” He shoved Aniya, a toddler, and Qunettia’s mother, Anqunettia, to the floor and rushed to his girlfriend to roll her off the baby. Blood soaked through her white T-shirt as she crawled down the hallway and slumped against the wall, a fiery pain surging across her back. As Anthony pressed a towel to her shoulder, she drifted in and out of consciousness.

Anthony ran to the door and called out: “My girlfriend’s been hit! Hurry! She needs help!”

Two police officers were already in the apartment complex and heard the shots. They raced up the metal steps and helped Qunettia to the couch. Bullets littered the kitchen countertop. One pierced a stereo speaker. Another shattered a picture hanging on the wall.

Officers ripped open Qunettia’s shirt to find a bloody, gaping hole above her left shoulder blade but no exit wound. They worried she might be bleeding internally. Paramedics strapped her to a stretcher and carried her down a flight of steps to a waiting ambulance.

Her thoughts were hazy, but she could make out the yellow police tape. Panic set in as she realized her apartment was the crime scene.

“I thought, ‘I must be fixin’ to die.’”

TIRED OF CRIME: Rochelle Jackson and her baby Roamia Jackson slump wearily in a friend’s near empty apartment as she talks about the absurdity of frequent crime incidents in the Clementine neighborhood. “They need to shut the whole apartment down,” she said.

For most Memphians, the real impact of the city’s generations-long struggle with crime creeps into their homes through the nightly news; another street-corner shooting, another stranger murdered.

But crime is frighteningly personal for Qunettia Robinson and thousands like her — they live with it.

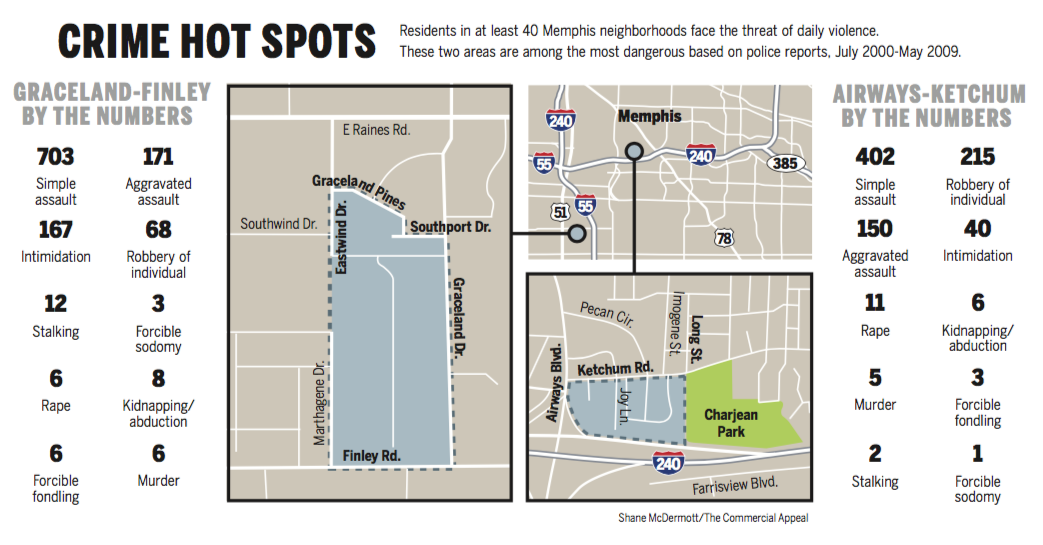

Across the city, more than 30,000 residents in roughly 40 neighborhoods — scattered from Hickory Hill to Frayser—live with the constant threat of violence, according to an examination of a decade of police records by The Commercial Appeal.

These are neighborhoods where a violent crime occurs one to three times every 10 days; where there are more than three violent incidents per every five residents.

But the stats, frightening as they are, don’t impart the horror of it all.

In South Memphis, a baby is delivered a month early, in July, when his mother is struck by a stray bullet.

In Frayser, police find a man lying face down, shot dead, in the parking lot of a BP Gas Station in August.

In Hickory Hill, three people are shot in a nightclub in September in what police suspect is an attempted robbery.

In many instances, victims are trapped by economics; they simply can’t afford to flee. In 2000, median household income in these danger zones was 35 percent lower than citywide.

Qunettia grew up in the old Fowler Homes housing project on E.H. Crump Boulevard. When she was ready to go out on her own, she chose the apartments on Clementine because rent was income-based. She paid only $212 a month.

The newspaper’s analysis shows the worst types of crime — including murder and aggravated assault, abduction and forcible rape — have steadily increased in her neighborhood since 2001. And despite a 10 percent dip in incidents from 2007 to 2008, violent crime still surged 120 percent over nine years, with 1,342 incidents in all.

“Clementine was a war zone when I was a rookie in 1990,” said Lt. L.D. Carson who works in the Airways precinct. “Not much has changed.”

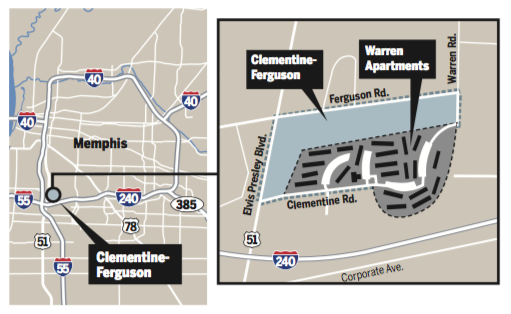

GROUND ZERO:

Less than two miles from the nation’s second most visited home — Graceland— the Clementine-Ferguson neighborhood is far less hospitable. An analysis of MPD incident reports this decade concludes the neighborhood — essentially a 248-unit apartment complex and a smattering of single-family homes and duplexes — is among the city’s most violent.

Built in 1970, the 248-unit Warren Apartments on Clementine sit off Elvis Presley Boulevard just north of I-240 and less than 2 miles from the second-most-visited house in the nation, Graceland.

Lining the drive along a dead-end street, the wood-frame and brick-veneer apartments look like many other complexes across the city. Security guards patrol the private property, and residents hang out on porches and in parking lots.

“If you roll in in the daylight, it’s pretty calm, not much going on at all,” Carson said. “In the daylight you look at it and think, ‘That’s not too bad.’ My first impression is just people hanging out, people who are idle and have nothing else to do but think up things they shouldn’t be doing.”

The Clementine area has long had a reputation for crime, so much so that residents wonder whether the complex was built on an old cemetery. Something more than human nature must be involved, they contend, for people to act so crazy, though county land records show no graveyard on that spot at least as far back as 1938.

“If you meet a friend Downtown or something and you tell them you live on Clementine they’ll say, ‘Oh, well, I’ll meet you at your mama’s house then,” said resident Latiffany Parks.

Sitting in their living rooms, residents discuss the crimes in and around the complex as part of neighborhood gossip.

Can you believe they robbed the ice cream man? or Did you hear they beat up that old guy and tried to steal his car?

Since 2005, eight people have been murdered in and around the neighborhood. Last summer, a man shot his brother in the forehead in an early - morning dispute over drugs.

Residents still talk about a 2005 murder in nearby Alcy Park when a passerby heard a man’s cell phone ringing and found him slumped on a swing, bleeding from a gunshot wound to the back.

Last year, a man was sentenced to life in prison plus 50 years for a kidnapping and murder on nearby Carlton Road. That one involved a Mexican drug cartel.

When Judge Lee Coffee sentenced Daniel “Chino” Lopez, he expressed a lament shared by some in the neighborhood: “We’ve become more like Beirut or Iraq with these acts of violence committed in broad daylight. People with guns are bringing war to the streets of Memphis, Tennessee.”

MAKING THE BEST OF IT: Jonathan Patterson tumbles on an old mattress outside a trash bin. Gunfire is so commonplace, residents are nonchalant about it, said Lt. Brad Newsom of the Airways precinct, “If we were somewhere in East Memphis and someone fired off a couple of shots everybody would go inside,” he said. “Not here. People are still hanging out. Kids are outside.”

On a recent summer afternoon, a couple of young boys made a trampoline out of old mattresses discarded near a trash bin at Warren Apartments. The heat of the day sent most adults indoors, though a few shot dice or smoked while they talked.

As the sun sets each night, tenants say, the atmosphere changes. More people migrate outside, lean on the railings, and stand in the grassy areas between buildings. Teenage girls walk barefoot on the concrete and matted grass, sparse and dusty with so much foot traffic. And young men drift to the path at the back of the complex that leads to the store on Warren.

One quiet August night, two women sat in kitchen chairs on the balcony overlooking an area of the complex residents call ‘The Hill’ — where the drive ascends before making a final turn.

“When you see a crowd, you know it’s time to go because you know they be sellin’ drugs, shootin’ dice or fixin’ to get into it,’’ said one woman who refused to give her name, fearing for her life.

If there’s a crime of opportunity, someone will take it, residents say. Purses have been snatched, cars broken into, vehicle parts stolen, apartments burglarized.

During the second week of September, a gun discharged during an argument that started over a pair of stolen baby shoes.

Thieves pry open mailboxes with butter knives, residents say, looking for checks and other personal information, especially at the beginning of the month.

Residents are afraid of gang members too — Gangster Disciples, Bloods, but especially the Kitchen Crip Gang. Some call Clementine “Cripintine” and tattoo the moniker on their bodies.

“They should be the security,” said Jessica Dillard, who moved to Clementine from Cleaborn Homes. “They in charge.”

People sell dope, shoot guns, she said: “It ain’t no safe place for nobody’s kids. Once they start shootin’, we say, ‘Oh, that’s a 9 (mm). That’s a 40 (caliber).’”

Recently, Lt. Brad Newsom, also of the Airways precinct, responded to a shots-fired call in the 1300 block of Clementine. He drove slowly through the complex with the window of his police car rolled down but didn’t see any commotion. Criminals know all the paths out of the neighborhood to elude police, he said, the ones that lead to the neighborhood on Ferguson or out to the interstate.

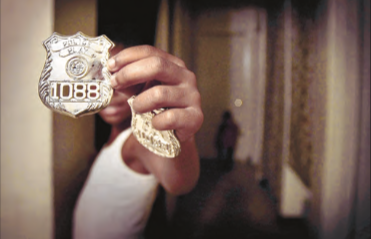

CHILD’S PLAY: Karshala Hill flashes a toy police badge while playing with her little brother in her grandmother’s apartment.

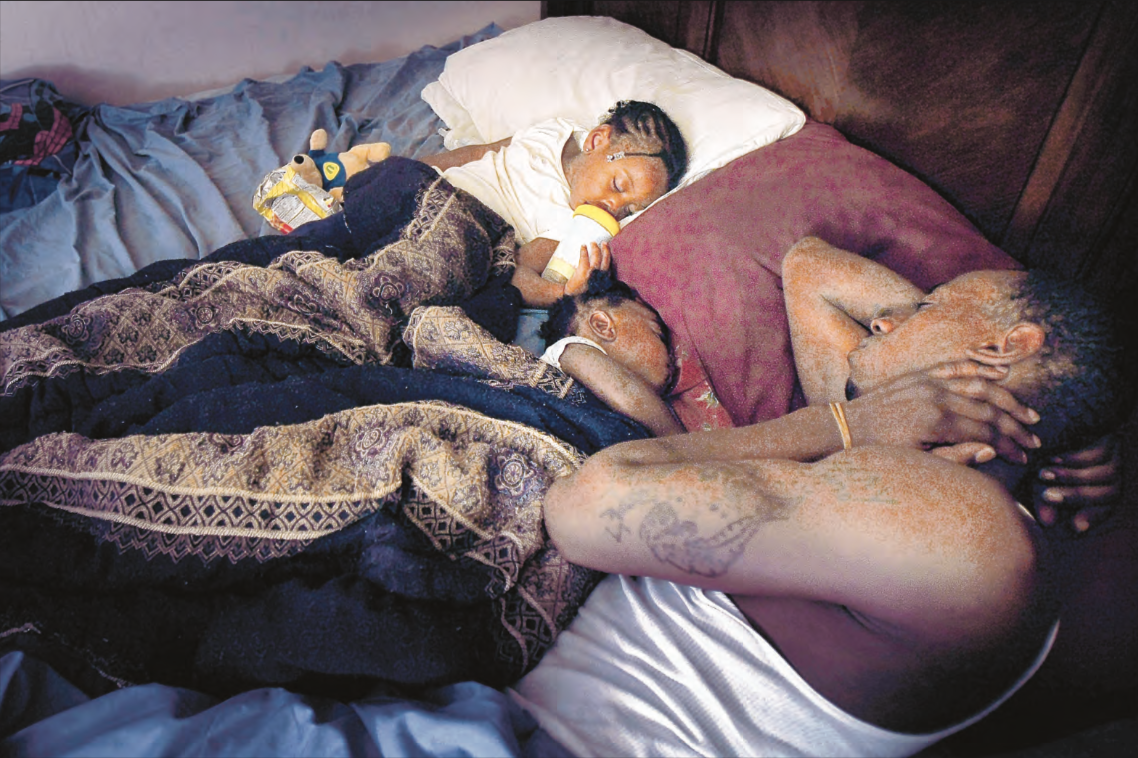

UNEASY REST: Anthony Seay Jr., Qunettia Robinson’s boyfriend, keeps the children — toddler Aniya and baby Anthony Seay III — close after their mother was hit by a stray bullet from a gunfight outside the apartment

‘IT AIN’T NO SAFE PLACE FOR NOBODY’S KIDS’

Young men standing in small groups dispersed. One child waved at the officer but most adults ignored the squad car. Nobody flagged him down to say where the shots came from. But he could guess what they might have been about. Most calls to the complex, he said, are about three things: domestic violence, drugs or money.

“If we were somewhere in East Memphis and someone fired off a couple of shots everybody would go inside,” Newsom said. “Not here. People are still hanging out. Kids are outside.”

Det. Paul Sherman, coordinator of the Police Department’s undercover unit, said his officers recently completed a clandestine operation in the apartment complex, buying crack cocaine from numerous sellers, and expects indictments before Christmas.

“We ’re fixin’ to take some of them down,” Sherman said. “It’s coming.”

Raymond Tucker, deacon at the New Harvest Missionary Baptist Church on Warren, said he used to minister to church members who lived in the Warren Apartments, but they’ve all since died. He no longer walks through the complex, but prays for the whole community.

“This younger generation is a new breed,” he said. “You really cannot approach them like you can older people because they have no regard for life. They have no respect for themselves or other people.

“I’m just being realistic — if you go over there and start to minister, first of all they don’t want to hear it. And then, again, a lot of them see you as prey, an opportunity to take advantage of you while you’re in there because nobody is going to tell the authorities who did what. It’s a code of silence.”

Lisa Gooden, community manager at the apartment complex, said she had no comment.

Jacqueline Condrey, an investigator with the Shelby County District Attorney’s Office who is in charge of the drug dealer eviction program, said she has a good working relationship with apartment management.

“Basically they have a zero-tolerance policy in their apartment complex when it comes to drug sales,” she said. “On the cases that I’ve been involved with them, and I have cases going back to 2002, my notes were always, ‘Tenant will be evicted under zero-tolerance policy’ or ‘Landlord has already filed FED,’ a forcible entry detainer warrant. That’s the name of the court-ordered eviction papers.”

BATTLE SCAR: Qunettia Robinson still carries the evidence in her shoulder from the night a stray bullet pierced the wall of her apartment. Neighbors, trying to explain the unending violence there, wonder if the apartments might have been built on a cemetery.

For weeks after the shooting, Qunettia Robinson wo u l d n ’t let her children out of sight. They couldn’t play in the living room. Instead, she took their toys into a cramped bedroom.

She stayed panicky and startled easily with every outside noise. Relatives called all day to ask: “Are you OK?” She hasn’t gone back to her janitorial services job.

Qunettia had constant reminders of the ordeal, both visible and physical. Across from the couch in the living room hung the picture frame with a bullet hole in the glass. And in the kitchen, she stared at another in the cabinet above the microwave every time she made the baby’s bottle. She got tired of trying to explain to her children what happened or distract them with movies and trips to relatives’ houses.

“It’s gonna happen again,” she said. “Someone is gonna move into this same apartment ... and then the same thing is gonna happen again.”

PACKING UP: Tired of being afraid for her family, Robinson moved out of the apartment, earlier this month. But she still has a bullet lodged in her shoulder and she fears for future tenants. “It’s gonna happen again,” she said. “Someone is gonna move into this same apartment ... and then the same thing is gonna happen again.” Photo by Mark Weber

In early October, fear drove Qunettia away. She moved to a new place not far from Clementine. She trashed the picture frame shattered by the bullet. No need to hang on to that memory.

There’s one thing, though, that couldn’t be left behind, something that will stay with her forever — the mangled .40 caliber bullet lodged in her shoulder.