Orphans come back to ‘The Home’ that took them in when no one else could

(From left) Masonic Homes of Kentucky alumni Joe Morrison, Joe Staten, and Eugene Blanton stand together on June 16, 2017.(Photo: By Michael Clevenger, C-J)

Staten heard the stories growing up. But he was always skeptical of that one.

“I kind of, at times, have suggested — and I don’t like to say this: He just had his eighth kid and no job, no money,” he said. “I think he might have helped it along. You know what I’m sayin’? But nobody really knows.”

With eight children, his mother, Mary Frederick Staten, had no choice but to send the older ones to the Masonic Widows and Orphans Home. With no Social Security or other public safety nets, it was their only chance.

Masonic Home alumnus Joe Staten. June 16, 2017 (Photo: By Michael Clevenger, C-J)

The Home had a rule: Children had to be 4 years old before they could enroll. So in 1931, when Joe turned 4 and his older brother Bill was 5, Mary Staten left the last of her children at the Home. She wanted the pair to go together.

Behind the story: What is a Mason?

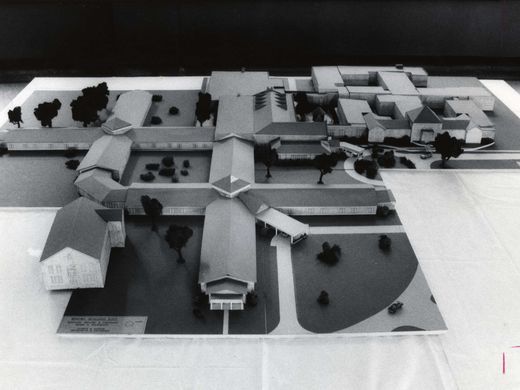

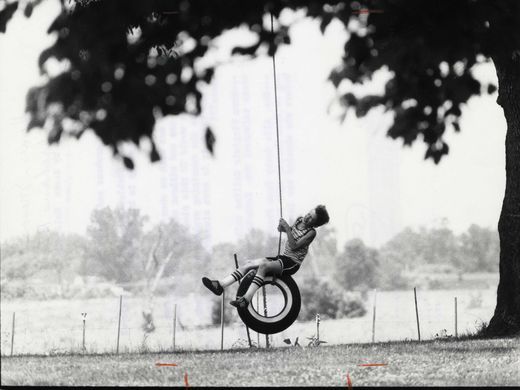

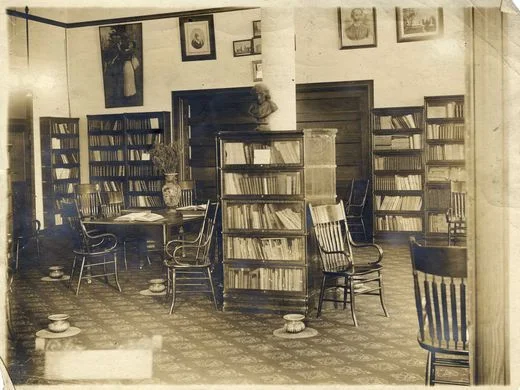

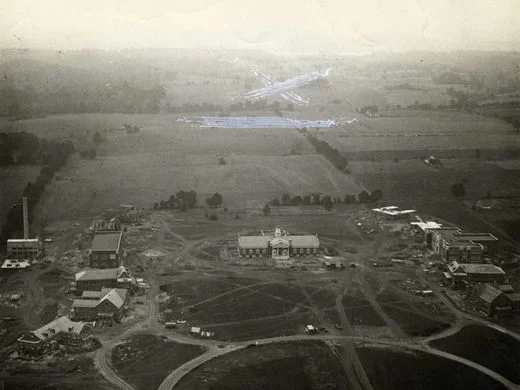

Photo gallery: Masonic Homes of Kentucky through the years

Timeline: History of the Masonic Homes of Kentucky

Mary Staten didn't show much emotion and wasn't an affectionate woman. But she must have felt incredible heartbreak. She just never showed it, Staten said.

"I think she put on a brave face because her life was very hard," he said. "... She just didn't want us to see it, maybe."

Mary Staten could read, but she only finished eighth grade. She had no skills and certainly no money. Nobody had any back then. It was the Great Depression when the country was pockmarked with bread lines, closed factories and “Hoovervilles” — makeshift encampments so named for President Herbert Hoover — where homeless families sought shelter.

“I didn’t put up a fight,” Staten said. “I just went to join my brothers.”

“I kind of, at times, have suggested — and I don’t like to say this: He just had his eighth kid and no job, no money. I think he might have helped it along. You know what I’m sayin’? But nobody really knows.”

By the time the youngest Statens arrived, hundreds of children had already found a haven there — dating back to the earliest days of Reconstruction when Kentucky Masons envisioned a place that could care for the widows and orphans of the Civil War. They’d welcomed even more during World War I and the influenza epidemic of 1918.

For Staten, life at the Home was regimented. Fourteen identical beds and chairs in the dormitory. A steamboat whistle attached to the boiler room for morning wake-up call. A job for even the smallest child: Dry mop a dormitory, clean the washroom bowls. Then off to school.

Orphans had two sets of clothes, one to wear and one to wash, with their names sewn inside. A house mother lived in each cottage to watch over them. Ms. Barbour, Ms. Gash, Ms. Johnson.

By seventh grade, boys started vocational training. They worked in the print shop or the shoe shop. And some worked the farm — with pigs and cattle and every vegetable a kid could name. The girls waited tables in the dining room, washed laundry and learned to sew.

But the Depression that brought so many Kentucky families to their knees barely registered within those walls. The children had three big meals a day and as much milk as they could drink.

The children got high quality health care and Christian teaching, too. During daily devotion, Staten recalled, the boys were always eager to share their favorite Bible verses. Invariably, it was the same one: “Jesus wept.”

“We were a bunch a rotten guys, I tell ya,’” he said, laughing at the memory.

So many children to play with eased the heartache. And there was always mischief to make.

Superintendent James Morris, or “Big Jim” as the kids called him, had a peculiar way with discipline. If he caught a child smoking, the punishment was to chew on his cigar. Stealing canned peaches meant a dose of castor oil.

They watched out for “Old Lady Morris,” too, who guarded an imaginary line that split the campus in two, dividing girls from boys. No fraternizing allowed.

“Some of us never did find that line,” Staten joked.

Joe Staten lived at the Home for 13 years. He missed his mother in the early days, but she came to visit on weekends with a sack full of fruit and cookies. And as he got older, he found that he’d rather be at the Home because there was more to do.

“All I can say is that it’s the greatest thing that ever happened to me because I don’t know what would have happened if it hadn’t been for that,” he said.

Staten was 12 years old and had moved on to the next cottage for junior high boys by the time Joe Morrison arrived in 1939. Morrison was just 3 years old, the minimum age then, and the youngest kid on campus.

His father, Harry Morrison, a member of the Meeting Creek Lodge 641 in Hardin County, had died during the ’37 flood from pneumonia. Because of high water, he couldn’t get to a doctor, and the doctor couldn’t get to him.

Morrison’s mother, Lucille Parsons Morrison, went to work in the laundry at Fort Knox and lived on post. A distant cousin, also a Mason, took him to the home.

Masonic Home alumnus Joe Morrison. June 16, 2017 (Photo: By Michael Clevenger, C-J)

“As a 3-year-old, I’m sure I cried every night,” he said.

But over time, the Home became a place of stability. He and the other children had opportunities they wouldn’t have had otherwise. The boys played basketball, the girls, field hockey. There was a Boy Scout troop and a glee club. And even an orchestra. Any child who wanted to play an instrument could take lessons. Morrison played the trombone.

After supper and on weekends, there were made-up games like “Shinny,” a stickball match that basically had no rules and another called “Go, Sheepy, Go,” akin to hide and seek.

Everybody seemed to have a nickname: Drain Pipe, Round Head, Big Kid. Morrison was Motley because he was so uncoordinated.

The matrons took the younger kids to the matinee at the Vogue Theater on Saturdays. But once the orphans reached high school — as long as they signed out — they could go just about anywhere on their own. Crescent Hill swimming pool. Louisville Orchestra concerts at Memorial Auditorium.

“They’d give every high school kid two car checks,” Morrison said. “And after lunch, we’d all get in the bus, ride down to Fourth Street, transfer to a streetcar and go out, watch the concert and come back by ourselves.”

The buses were trolleys back then: “In the winter time they’d freeze up, and boy, those sparks would fly.”

When Morrison was 14 — and the runt of Cottage Four — the other boys often conscripted him for certain top-secret tasks, like climbing through the bars of a window to get canned peaches another kid had put in the ice house.

“I got drug outta bed and shoved between those bars because I was the only one that would fit,” Morrison said. “… And, of course, they would run off with the peaches. I never got any. Not one. In fact, they wouldn’t even help me out.”

““I would say that I felt underprivileged. But when I got out in the real world, I found out we had everything we needed.””

It was the same drill for ‘rasslin’ on Tuesday nights. The kids weren’t supposed to watch TV except in the dining room on weekends. But they’d drag Morrison out of bed and hoist him on their shoulders to an unlocked window so he could climb in and open the door. Then a pack of boys poured in for the show. But he went back to bed.

“I was scared to death they’d get caught,” he said.

The matrons made the holidays special. Every child picked two Christmas gifts from a list. A cowboy suit, a wind-up train on a track, roller skates, and every teen’s favorite: Chuck Taylor All-Stars and a satin blue and gold warm-up jacket, the Home school’s colors.

In 1947, Morrison saw significant changes with the arrival of Superintendent Luther Goheen. He erased the imaginary line dividing the campus so the children could be more social. Goheen hosted Halloween dances and allowed the boys and girls to eat together.

When Morrison turned 15, his mother met a soldier at Fort Knox and got remarried. So in 1951, he had a home to go to in Hardin County. He’d been at the Home for 12 years. During his time away, he missed his family dearly and couldn’t wait for the school year to end so he could see them over the summer.

“I would say that I felt underprivileged,” he said. “But when I got out in the real world, I found out we had everything we needed.”

Marvie Bloodworth Wicks came to the Home a year after Morrison, in 1940. But nobody ever called her Marvie. When she was born, her father, Prentice Bloodworth, said at three pounds she was no bigger than a cricket. And the nickname stuck.

Prentice Bloodworth was a farmer and a Mason in Franklin Hollow. One morning, when Cricket was 7 months or 8 months old, he threw kerosene into the fireplace to heat their small country house before everybody got up. Flames blew back, burned him and burned the house down. He carried her to safety just in time. Cricket's three older siblings ran out with their mother.

Prentice Bloodworth only lived a few days. But before he died, he told his wife to send all of his children to the Masonic Widows and Orphans Home in Louisville.

Cricket Wicks was a resident of the Masonic Home. June 23, 2017 (Photo: By Michael Clevenger, C-J)

Cricket’s mother, Ora Mae Weaver Bloodworth, tried babysitting. But the 50 cents a day she earned wasn’t enough to keep the family together. So she moved to Michigan to work at Ford Motor Co. Little Cricket stayed with her grandmother until she was old enough to enroll.

Though she was just a toddler, Wicks remembers her first day. She’d never seen an indoor toilet. Back in Franklin Hollow, they’d only had an outhouse. So she asked some older girls how to use it.

“I guess that tickled them,” she said. “And they all started laughin.’ And I thought, ‘Well, I’ll show them.’ So I just did it on the floor. And, of course, the girl that took care of me had to be the one to clean it up.”

Not long after Wicks’ arrival, the Great Depression gave way to World War II. The campus bustled with outsiders, as the orphans called them — women from the Red Cross sitting at long tables making bandages. There were the sugar rations and air raid sirens.

“We would hear the sirens, and we’d run and get in the hall,” she said. “And the lights would be out, and we’d lean against the wall and sit down and wait for everything to be over. And then we’d hear planes flying overhead. We thought it was the actual war.”

“I guess that tickled them. And they all started laughin.’ And I thought, ‘Well, I’ll show them.’ So I just did it on the floor. And, of course, the girl that took care of me had to be the one to clean it up.”

Marvie Bloodworth Wicks, who was known as Cricket

But they still had everything, she said — clothes from the big department stores downtown, trips to the circus and ice skating rink, candy to eat and pocket money to spend.

There were regular shenanigans. Like at first snowfall when the kids dragged their bedsprings out of the cottage, over the fence and up the hill of the 5th hole at Crescent Hill golf course. The handrails were perfect for sledding. Or the time one of Cricket’s friends got a splinter in her behind after the girls dragged each other on towels to wax the hardwood floor.

And then there was Laura Johnson, the teacher beloved by every single orphan at the Home. Sweet and tender, she had a special way with students. And her devotion didn’t end when Wicks left after 15 years in 1955.

Ms. Johnson called once a week to check on Wicks, who was studying at the business college. When Cricket complained she was often late to class because she had to wait tables for extra money, she soon received $10 a week in the mail. Ms. Johnson sent her own money.

“I thought she dearly loved me,” Wicks said. “Well, then I found out later that she was treating every kid the same. And that’s why we were so crazy over her.”

Wicks wonders what her life would have been if she’d stayed in that small town. She wouldn’t have gone to school, surely, and might’ve been married by age 13 or 14.

“No tellin’ what would have happened to me,” she said. “I’ve thought about that quite a bit.”

Tears come hard and fast when she thinks about her most formative years there.

“I still think of it as my home,” she said. “And the kids as my family. It was just like they were your brothers and sisters. And I just loved it all.”

Eugene Blanton arrived in 1950, the start of what would become America’s decade of prosperity. But Blanton’s family in Harlan County had been living a scant existence.

Blanton’s father, Jesse Blanton, drove a road grader for the state. One day, in 1949, the brakes failed. Instead of going over the edge, he slammed the grader into the side of Pine Mountain. The crash knocked him out. He fell out of the grader, and one of the tires caught him. He died in the back of a pickup on the way to the hospital.

Blanton remembered one of his father’s co-workers, a preacher, walking up the gravel road to their four-room, wood-frame house that 11 people called home.

Masonic Home alumnus Eugene Blanton. June 16, 2017 (Photo: By Michael Clevenger, C-J)

“My mother was a basket case,” he said. “She couldn’t talk. All she was doing was just crying.”

At age 11, Blanton was too shocked to cry.

Roberta Nolan Blanton had no choice but to send her children to the orphans' home. She was a country housewife in a home with no electricity or running water. She directed the boys to fetch water from a spring and firewood or coal for the stove. And she steered the hand plow.

So she and eight of her children — the ninth was too old — went to Wallins, a little town that had a Greyhound bus station. Until that day, Eugene Blanton had never been on a bus and had only once been out of Harlan County.

He didn’t know quite what to expect, but he knew he was never going home.

“You’re leaving the only place you’ve ever known,” he said. “I wasn’t terrified, but it had my attention.”

“I thought I’d died and gone to heaven. I slept well, but sometimes I cried because you lose your family life. And you don’t know the emotions you’re having down inside. Everything was changing so fast.”

It took all day before the bus pulled into Louisville. Some boys from the Home picked them up in a station wagon and took them straight to the dining hall for dinner. Blanton couldn’t believe his eyes — two-story brick buildings with slate roofs. Gold flecks in the marble hallways. It was so different from the life he’d known — eating what they grew in the garden, wearing clothes his mother made from empty Martha White flour sacks.

“I thought I’d died and gone to heaven,” he said. “I slept well, but sometimes I cried because you lose your family life. And you don’t know the emotions you’re having down inside. Everything was changing so fast.

“But you had kids that had been through it already waitin’ for ya’. It’s just sometimes you start thinking too far in the future and you start longing for the past.”

Blanton stayed for seven years. In all that time, he never wanted to go back home to the coal fields in eastern Kentucky. He left in 1957.

“I’m sort of proud of it,” he said. “I don’t try to hide it somewhere. Those people, they raised me. And they taught me a trade that I could get a job and so forth. That’s a pretty good start.”

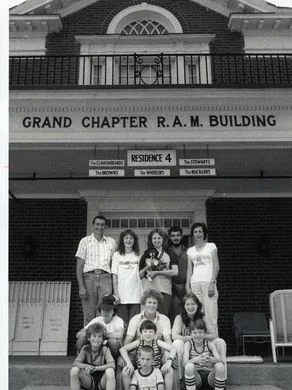

Ten years after Blanton left, in 1967, the Home celebrated its 100th anniversary. Numbers dwindled over the next two decades until the last orphan left in 1989, and the Home started focusing on senior care.

But for the orphans who lived there during some of the nation’s — and their own families’ — worst tragedies, it was a place that transformed their lives. It gave them stability and set them on a path for fruitful futures.

Joe Staten went on to serve on the USS Copahee, a Naval escort carrier in the South Pacific, and came home to work for LG&E. He married and had six children. Joe Morrison worked at Citizens Fidelity for 30 years and retired as a vice president. He’s been married for 58 years. Cricket Bloodworth Wicks went to secretarial college and later earned degrees in library science, history and teaching. She had a son and has been married for 61 years. Eugene Blanton joined the Air Force and worked for Fischer Packing Co. for 28 years. He had a daughter and has been married for 46 years.

All this time, the orphans’ affection and fierce devotion for each other — and the Home that took them in when no one else could — remain.

Originally published in the Courier Journal