Thin ranks, high risks

Assistant Public Advocate Melanie Lowe discusses the case with one of her clients at the Oldham County courthouse. Aug. 13, 2015

Stretched to the brink

NOTHING HAPPENS FAST ENOUGH

Assistant Public Advocate Melanie Lowe finishes paperwork in her office before heading to the Shelby County Detention Center. Aug. 13, 2015 (Photo: Scott Utterback/The C-J)

Dawn has barely broken, and Melanie Lowe is already in a hurry.

She’s on her way to court. A familiar route, timed to the minute. Jericho Road to avoid the train. Burks Branch to skip the lights. She scarfs a protein bar and dials a colleague. No, she can’t cover for another public defender in juvenile court. Too many cases.

Assistant Public Advocate Melanie Lowe finishes paperwork in her office before heading to the Shelby County Detention Center. Aug. 13, 2015

(Photo: Scott Utterback/The C-J)

For 27 minutes Melanie zips over two-lane roads, the back way through Shelby County. She slips into a parking spot half a block from the courthouse and pops the trunk. Her coffee’s already lukewarm. It’s five minutes to 8. Just enough time to quiz herself on the day’s cases. There’s nothing worse than having to ask a client: What’s your name? Standing at her trunk, she thumbs through green, color-coded files.

Restitution, review of treatment, plea. Sentencing, sentencing, arraignment. Child support. Sentencing.

“First appearance?” she asks herself over the swish and drone of passing cars. “So – maybe – I don’t know. Maybe a rocket docket? Maybe not.”

Motion to revoke, sentencing. Pretrial conference, sentencing.

She needs to meet clients before Circuit Judge Charles Hickman takes the bench. The courthouse opens at 8, but a glitch with the automatic locks delays their release by four minutes, time she can’t waste. She checks her watch again.

Past security, Melanie scurries. She can’t walk fast enough. Can’t talk fast enough. Can’t get to clients fast enough. She double taps the elevator button. Nothing happens fast enough.

Melanie has more than 30 cases. But before day’s end, there will be more.

Her harried schedule underscores a problem the Kentucky Department of Public Advocacy has grappled with for decades: Too many clients and not enough money mean public defenders are being stretched too thin – putting the quality of representation at risk.

Tim Young, chairman of the National Association for Public Defense, said the constitutional issues for indigent defendants across the nation are serious.

“It means people are going to prison for longer than they should. It means people are going to prison who shouldn’t. It means we’re spending vast sums of money incarcerating people who are not only innocent but never should have been in our system in the first place.”

Though no case has been filed in Kentucky, the national American Civil Liberties Union and its affiliates have filed lawsuits against other states, counties and municipalities contending that they have deprived poor people of their right to an attorney. In Michigan and Montana, for example, those efforts have already prompted legislative reforms.

“Any state where we think there are significant, systemic problems – and it sounds like there are in Kentucky – is a state we are going to be looking at very, very closely,” said Ezekiel Edwards, director of the ACLU’s criminal law reform project.

Kentucky has a problem

INADEQUATE RESOURCES STRAIN SYSTEM

In 1963, the U.S. Supreme Court issued a landmark decision, Gideon v. Wainwright, establishing that people accused of crimes have the right to an attorney regardless of their ability to pay. Indigent defense has been chronically underfunded nationwide ever since.

In Kentucky, public defender services received $49 million in state funds for fiscal year 2015 – less than half of 1 percent of the state’s overall budget, according to the department.

Assistant Public Advocate Melanie Lowe lets one of her clients know the date of his next appearance in court. Aug. 13, 2015

(Photo: Scott Utterback/The C-J)

The commonwealth’s problems are numerous, but they all hinge on inadequate resources.

• In fiscal year 2015 almost every staff attorney had a caseload that exceeded the maximum national standard. Only 13 public defenders didn’t because they either had additional management responsibilities or spent so much time on the road they couldn’t take on more. All told, the state’s public defenders last year handled 175,587 cases.

• Kentucky has 333 public defenders in 33 offices to cover every single court in all 120 counties. Some of those offices cover as many as eight counties, which forces some public defenders to drive thousands of miles each year just to reach courthouses, taking time away from arguing cases or talking to clients.

• At $38,770 a year, the commonwealth has the second-lowest starting salary for public defenders in the region, making it difficult to hire and retain lawyers. In contrast, Indiana public defenders start at $47,000.

• Public defenders admit that their heavy caseloads, which limit the time they spend with clients, have caused them to make mistakes.

Kentucky Public Advocate Ed Monahan said a large part of the problem is that more and more Kentuckians can’t afford private attorneys.

From 2006 to 2015, newly assigned public defender cases per year rose from 137,923 to 153,358 — an 11 percent increase.

So even as the state has experienced a drop in crime, public defenders are being appointed more often.

“When you’re talking about criminal defense in Kentucky,” Monahan said, “you’re talking about public defenders.”

Completely overwhelmed

'HERDING CATS' IN THE COURTROOM

In Judge Hickman’s courtroom there’s no time for chitchat. He calls cases rapid fire in Shelby County: Commonwealth v. Coleman. Commonwealth v. Combs. Commonwealth v. Coomer.

Melanie Lowe cocks her eyebrow, shakes her head and hunts for the right file.

Cases turn by the minute. A plea accepted. A sentence declared. A defendant’s fate decided.

8:25 – Melanie looks for clients in the courtroom: Mr. Perry? Ms. Gardner? Ms. Buck? Ms. Coleman? Nobody has shown up.

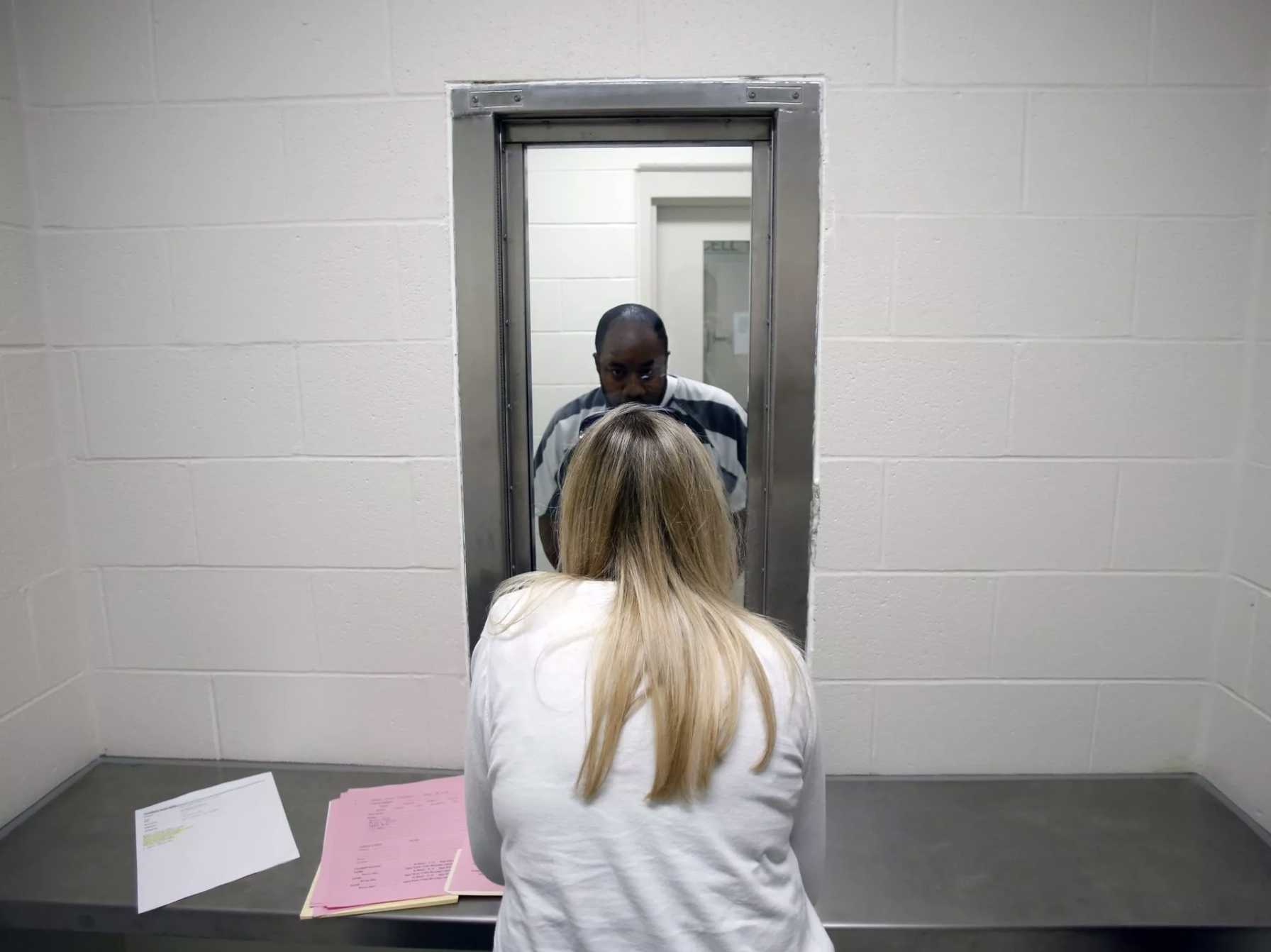

8:27 – Melanie barrels down the steps. She meets clients in a tiny boxed conference room, glass between them.

8:31 – She waits for prison-striped jumpsuits to appear. “Herding cats,” she says.

8:35 – The jailer brings a rocket docket case. No paperwork. Looks at her watch. Judge is already on the bench.

8:39 – Ms. Decker? No, Ms. Wilson. Nobody’s in the right order. There’s an offer: three diverted for five years. No paperwork. It’s upstairs.

Assistant Public Advocate Melanie Lowe meets a new client at the rocket docket at Oldham County courthouse.

8:41 – She hustles upstairs for the file.

8:44 – Checks the clock. Hickman’s calling cases.

8:47 – Back in the box. Reviews a guilty plea. Presses the deal up to the glass and reviews every word. Client will take it.

8:57 – “Somebody get me Loretta Decker.” Doesn’t have time for a sob story. She interrupts: Phone number? Address? How long in custody? “Let me see what I can do.”

9:02 – Checks her watch. “I’m running low on time.”

9:11 – Someone in the hall asks about an adoption case. Call the office to set up an appointment.

9:21 – Back before Judge Hickman. Commonwealth v. Bynum.

9:28 – Fans her suit jacket. “Is it hot in here?”

All morning Melanie keeps pace. Argues before the judge. Runs downstairs for client conferences. Rushes back. “What’s your name?” she asks one prisoner. “Faces aren’t my strong suit at this point.”

Court adjourns at 12:46 p.m., and Melanie heads to her car. She reflects on her caseload.

“I feel completely overwhelmed and out of control in my practice most days,” she said

Shouldering the load

CASELOADS EXCEED NATIONAL STANDARD

In 2013, public defenders statewide were appointed to more than 70 percent of cases in circuit court, the court that handles the most serious crimes. In more than a dozen counties that number was 80 percent or higher.

“It’s obscene what we ask these people to do,” Monahan said.

According to the National Advisory Commission on Criminal Justice Standards and Goals, public defenders should handle no more than 150 felonies, or 400 misdemeanors, or 200 juvenile cases, or 200 mental health cases, or 25 appeals in one year. And that doesn’t count any other responsibilities.

Public defenders in Kentucky carry a mix of cases, and in fiscal year 2015 they averaged 448 newly assigned cases. That average was 24 cases fewer than in the prior year, but one state official put it this way: “That’s like going from Mount Everest to K2. It’s still way too high.”

That count doesn’t tell the whole story, however. It doesn’t include cases still open from the previous year, reopened cases or cases public defenders had to pick up because of a colleague’s medical leave or staff turnover. So far in calendar year 2015, 33 public defenders have left the department, and 12 of those spots are still vacant.

The phone never stops ringing

'YOU CAN TRIAGE ALL DAY, EVERY DAY'

At 41, Melanie Lowe doesn’t fit the movie role of a crafty, grizzled public defender. The petite blonde smiles with her whole face — sunglasses perpetually atop her head and gum in her mouth. She’s been a public defender for 15 years, working her way to a salary of $57,917.

Her mother may have unwittingly pushed her into the job. When Melanie was a child her mom set up play dates with the unpopular kids. Now, her toughest clients are often her favorites. It seems hardwired, she said. Otherwise, she might not be able to do it.

Yet she seems made for the job.

Assistant Public Advocate Melanie Lowe starts a recent Wednesday by pulling all of the cases she will be working on that day. Aug. 13, 2015

(Photo: Scott Utterback/The C-J)

Melanie’s swearing is infamous. Sometimes it’s enough to make clients blush. She’s a combination of country lawyer and straight-shooter without an ounce of condescension. “He’s wild enough to shoot at,” she’s known to say. But just as often: “You know I don’t make promises, but we’re gonna fight like hell on this.”

A client once described her as a “g—damn Barbie doll.” Some, especially parents of juveniles, wonder aloud when she’s going to be a “real lawyer.” Others ask directly if she gets paid to cut deals. But she has a reputation among inmates of being as good or better as any “paid attorney.”

Most days, her office feels like a swamped emergency room.

“It’s all triage,” she said. “You can triage all day, every day.”

The phone never stops ringing. Clients want updates. Others ask for appointments. Forensic experts explain evidence. Prosecutors talk deals. Investigators need direction. And sometimes the boss just wants to dish about the latest bad arrest.

“Do you know they broke down her door without a warrant?” Melanie barked into the phone one afternoon. “Exigent circumstances, my ass. That isn’t assault one. We need to be all over this.”

She perpetually apologizes to her police officer husband, David Stratton, for being late. For breaking promises to be home early. One more call turns into an hour or two or three. He handles supper for their 4-year-old son, Henry. Frozen pizza or a TV dinner. She misses bath time and PJs but usually makes it home in time to tuck him in.

Shortcuts to survive

DIFFICULT TO INVESTIGATE EVERY CASE

In fiscal year 2015, Melanie Lowe represented clients in 588 cases across four counties – Henry, Oldham, Trimble and Shelby. DUI, theft, assault. Robbery, sodomy, attempted murder. Some clients faced hard time. All were unable to hire private attorneys. And every single one looked to Melanie to save them.

With so many cases, Melanie, like many public defenders, takes shortcuts. Getting to jail to see clients is the hardest to squeeze in, so she cuts corners. She doesn’t mail letters to people who miss court anymore. And she finds it difficult, if not impossible, to investigate every case the way it should be.

So “you have to take those (shortcuts) in order to give the time to the cases that really need it,” she said.

And then there’s the unspoken expectation that public defenders are the catch-all to address holes in the system. She reads pleas to illiterate clients. There are never enough resources for the mentally ill or rehab beds for addicts. But she always hunts them down.

“Sometimes I’m a glorified social worker,” she said, “if there’s any glory to it at all.”

Clients have wide-ranging views about her skills. They know she’s busy, and many don’t expect much contact with her.

Erin Nelson, who has twice been her client, says Melanie saved her life by getting her into rehab for heroin addiction. Their first meeting was typical of Melanie’s schedule.

“You’ve got like five minutes before you have to go up in front of the judge,” Nelson said. “… She knows her stuff so she was going a million miles an hour, and I was like, ‘Can we go back to square one because I don’t even remember what you are talking about.’ ”

Despite all of the obstacles, Melanie doesn’t think her high caseload compromises the quality of her work. But that doesn’t mean she hasn’t made mistakes.

In one case she didn’t know an internal Department of Corrections regulation, which affected her client’s sentence. She called the prosecutor and admitted her mistake: “This guy got 10 years. It was supposed to be five. Let’s fix it.”

And more than once, she’s made an impassioned plea only to realize she was defending the wrong client.

“With this volume – Christ – you can’t possibly not make a mistake doing this,” she said. “It’s the human condition, and it’s the nature of this work.”

Caught in the hallway

CASELOADS AFFECT CLIENTS ACROSS THE BOARD

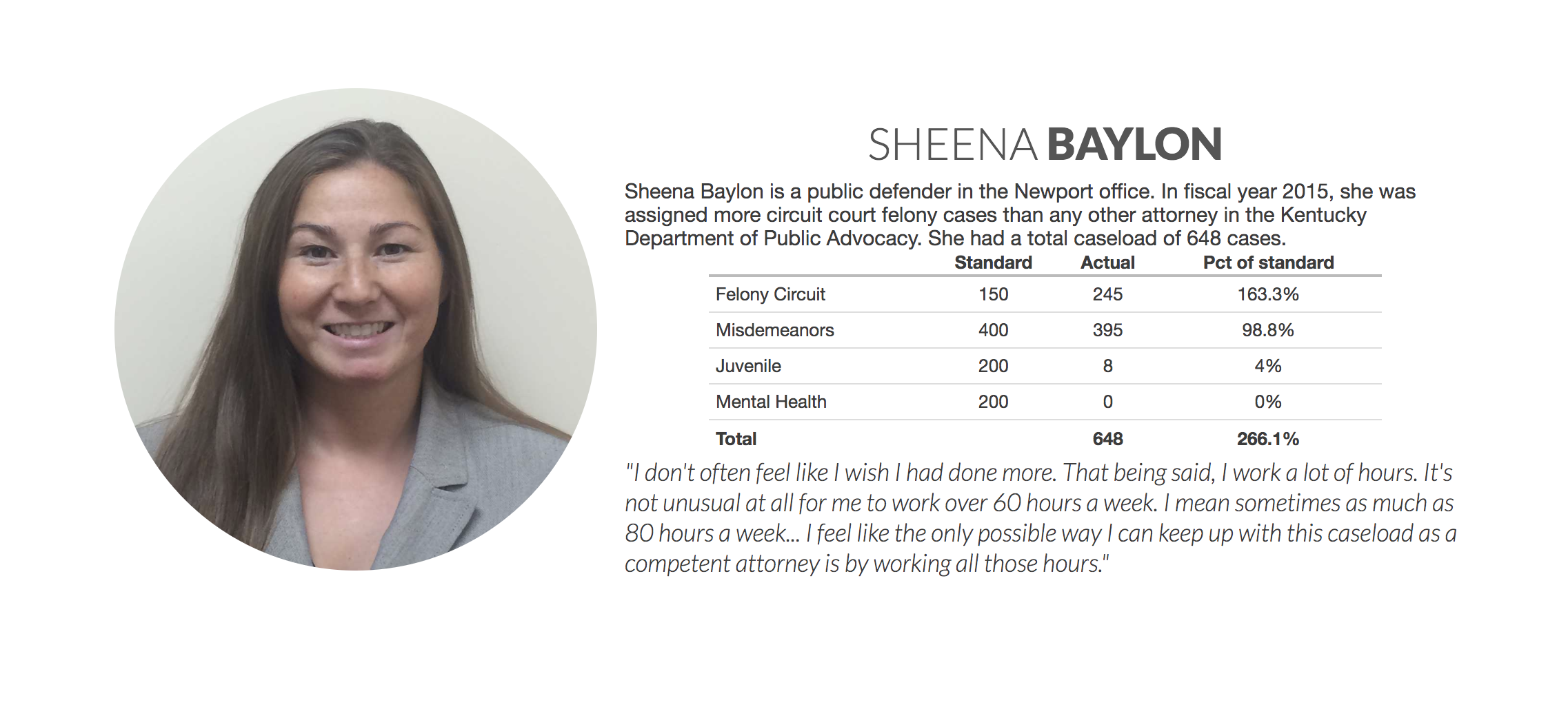

Other public defenders across the commonwealth also worry whether they’re doing enough for clients. Many have caseloads much higher than Melanie Lowe’s.

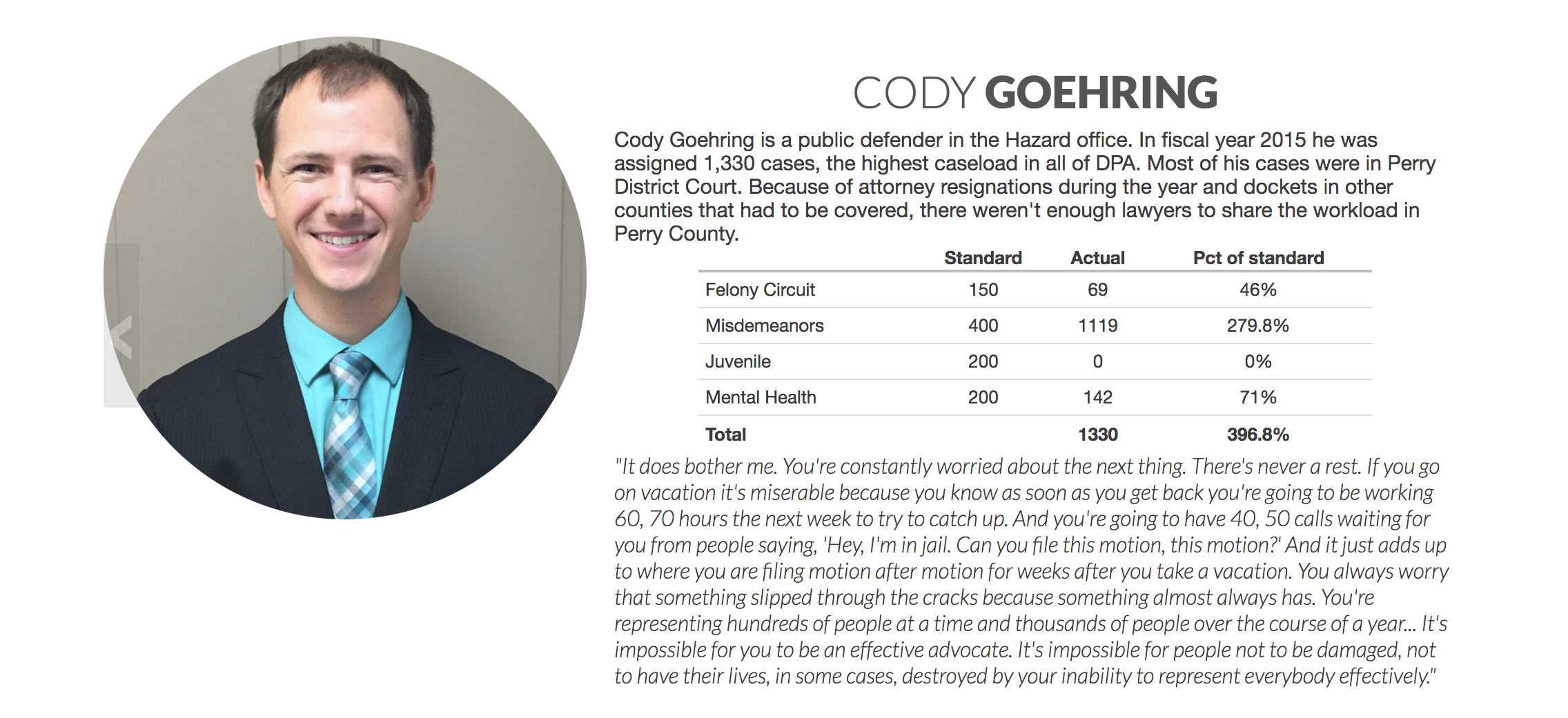

Cody Goehring, who’s been a public defender for two years, covers Perry District Court in the Hazard office. In fiscal year 2015 he had 1,330 cases, more than any other public defender in the department.

On pretrial conference days, he may have four hours to meet up to 55 clients in the courthouse hallway. “And I’ve never met or even spoken to the majority of them,” he said.

At the same time, the judge calls other clients he’s defending.

“At the very least the person is sitting in the courtroom wondering where the heck I am, and they’re in front of the judge trying to represent themselves when their public defender is out in the hallway,” he said.

His caseload affects clients throughout the process, he added.

“I will show up to the date of their pre-trial and I will not have filed the substantive motions because this is the first time I’ve ever met with them,” he said. “And a plea offer is given, and they plead guilty because they don’t want to have a jury trial … and the motion that would have gotten the case dismissed or excluded evidence that was unconstitutionally obtained is never filed.”

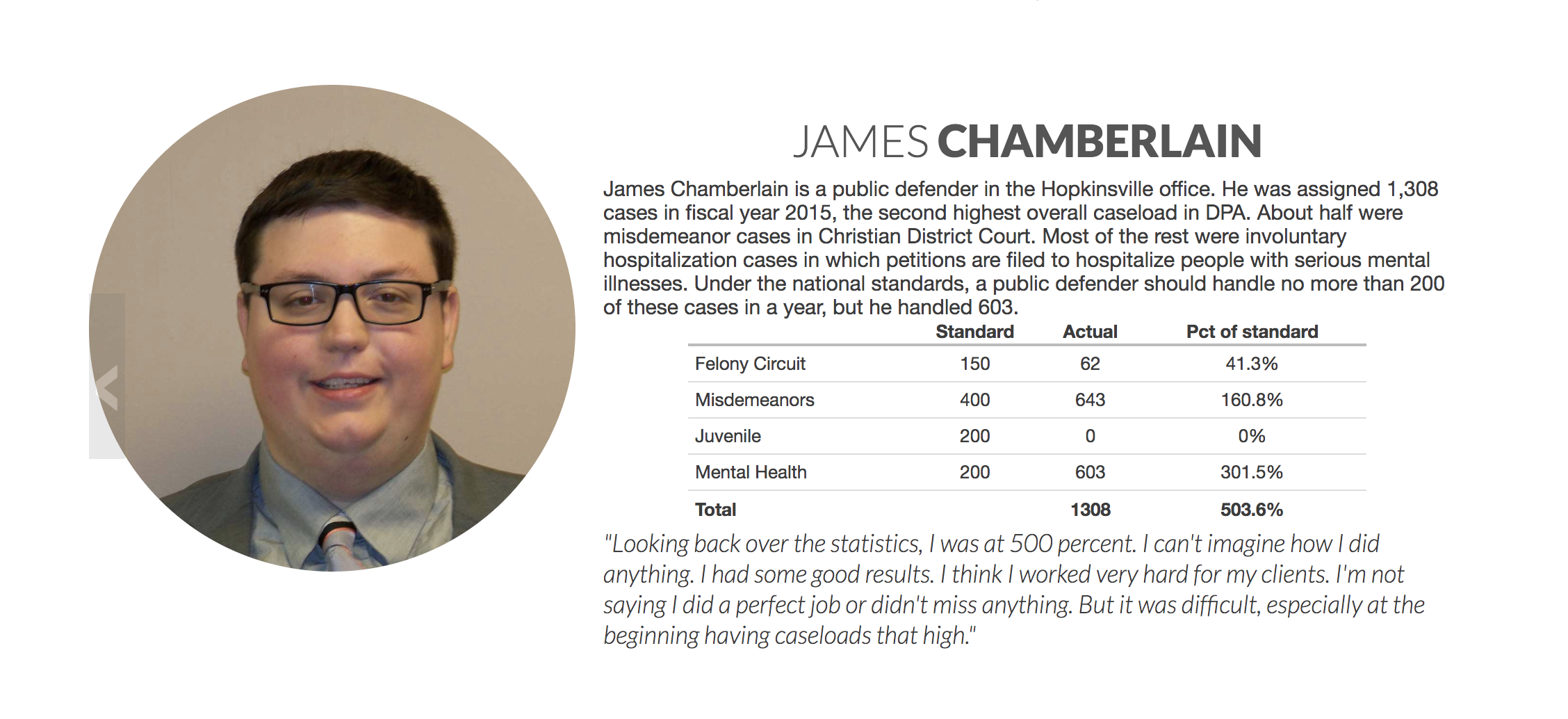

James Chamberlain, who covers both district and circuit courts in Christian County, has been a public defender for just over a year. There are 14 attorney positions in his office, but they’ve never been fully staffed. One week last year, he opened 150 new cases. From October to January he was in court every single day.

He doesn’t have time to visit the jail daily and worries whether he missed something. Recently, in a case that was ultimately dismissed, he found a suppression argument that should have been vetted – but not until he was prepping for trial.

“And that’s something I found,” he said. “There might be things I don’t find.”

He also worries about bond motions for clients who sit in jail.

“I might get overwhelmed, and I might forget to file a bond motion,” he said. “ … And because of my error he may sit in jail for two more weeks. And you know, it’s happened, and I regret that."

Pushing for people, resources

REMEDIES SOUGHT TO IMPROVE SYSTEM

The state Department of Public Advocacy has been fighting for more lawyers, more offices and more resources for a decade, but the process has been a bumpy one. One refrain has been that to improve efficiency, the state should fund 57 offices instead of 33.

“Our most costly resource is our intellectual capital, our attorneys, our staff,” said Monahan, the state’s public advocate. “And when we put them in a car a half-hour or an hour one way that’s low efficiency.”

He’s also pushing for pay raises. Among Kentucky and its seven surrounding states, only Missouri, at $38,544, has a lower starting salary. And after five years, public defenders in Kentucky earn $52,817 compared to $65,929 in Virginia and $74,251 in Illinois.

That makes it tough to recruit talented lawyers and retain them, Monahan said.

He also noted that an alternative sentencing program, which uses social workers to help low-level drug offenders with treatment, has offset costly jail and prison time. The department will employ up to 45 social workers this year, saving the state millions of dollars.

“That hasn’t helped us on the caseload side or the salary side ... but it has been a form of significant support for us providing a service that, really, nobody else in the system can provide,” Monahan said. “... But you can’t move everybody into it.”

Even without pay raises, the department would have to hire 115 new attorneys to simply meet the caseload national standard, an unlikelihood given the tight state budget and pension shortfall.

Reform legislation passed in recent years has been welcome, but Monahan is pushing for more, including changes to the penal code such as reclassifying minor misdemeanors to violations, increasing the felony theft limit from $500 to $2,000 and presuming parole for eligible, low-risk offenders — all of which would save the state additional money.

“It would somewhat reduce our caseloads,” he said. “The second thing is that it would create substantial, sustainable savings in the amount of money being spent on corrections at the county level and the state level.

“... Some of it ought to come back to the people who are out saving it. And that’s us.”

Watching the clock

NO BREAK IS COMING

On a recent Friday, Melanie Lowe learned a prosecutor wouldn’t accept her counteroffer on an assault charge involving a gun. So a case she expected to settle was set for trial – less than two weeks away.

“The minimum (the client) could serve on this is eight and a half years,” she said. “And he’s an older man. He’s in pretty good health, but he’s no spring chicken. This is not just eight and a half years. ... This could be some of the best years he has left.”

Melanie Lowe, her husband David Stratton, and their son Henry have some pizza for dinner after mom had a long day in court. Aug. 20, 2015

(Photo: Scott Utterback/The C-J)

She tossed and turned the following night, fending off nightmares. Her dreams were gibberish: She was in court. Couldn’t make sense of motions. Didn’t object to evidence. She felt incompetent.

That Sunday, Melanie played superheroes with her son while she waited for her husband’s shift to end. She needed to get to the office. She watched the clock, threw in a load of laundry. The triage was beginning again.

Once her husband arrived, Melanie hugged Henry and told him: “Momma’s gotta go to work now. I’ll be back in a little while.”

He hugged her tight, and his 4-year-old response broke her heart a little: “I’ll miss you while you’re gone, mommy.”

But she couldn’t tarry over his sweet expression. The clock ticked on the assault case. There was no break coming.

She had motions to file. An opening to write. Witnesses to find. Evidence to examine.

All in 12 days.

Originally published in the Courier Journal | Images by Scott Utterback