CHERRY’S CHOICE

Like a real family: Cherry smokes while watching family members romp at Shannon Elementary School’s playground during a rare family outing. Cherry said, “I want us to be better, like a real family. Like go out together, go to the park, go out to eat, go to the movies, walk on the river.”

One teenager faces long odds to escape drugs, crime and poor education as she stubbornly fights those obstacles to pursue her dream of a better life.

On a quiet street, a wiry teenager sits on her front stoop surrounded by a chain-link fence. In dark cursive letters, her mother’s name is tattooed just above the bend of her wrist, her own name inked on the soft side of her forearm.

She squints into the sun to trace the path of an airplane whirring overhead until she can no longer stand the glare. She closes her eyes, momentarily enjoying the quiet as smoke from her cigarette disappears over the rooftop.

It is on such rare, quiet occasions that Cherry Adams can imagine herself to be anything — anyone — she pleases. Chef. Poet. Band director. Veterinarian. Choreographer. World traveler.

She can see herself in cap and gown, accepting a title not yet bestowed on anyone in her family: high school graduate.

Suddenly, her dad shouts from inside the house, interrupting her muse.

“Che-rrry!” he yells.

“Sir?” she calls back.

The buzzing plane and bright sun disappear as she dips her head under the awning, bringing into focus the life into which this 16-year-old was born.

'I HOPE I SURVIVE TO 15'

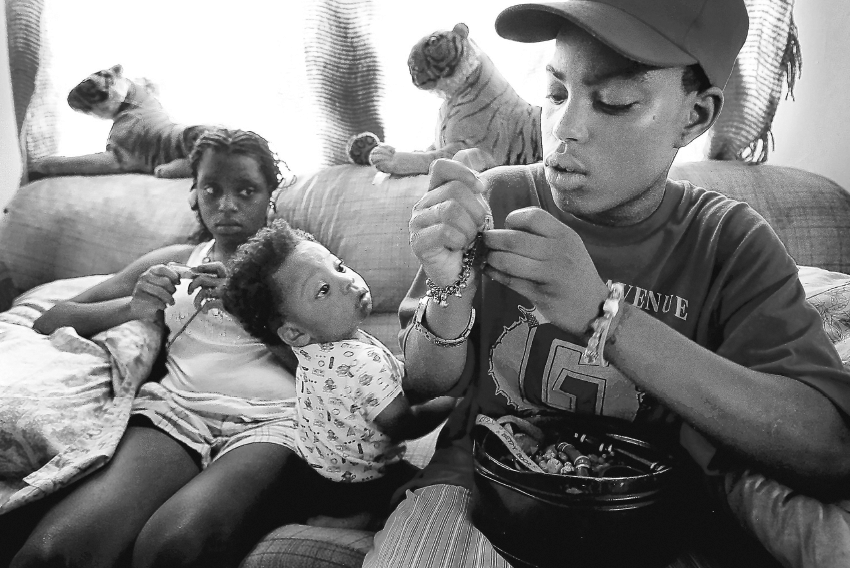

DREAM BIG — Cherry Adams, 16 (right), lives in a crowded family home in Hyde Park that includes older sister Destiny Benson and nephew Maricus. Though there is laughter in the home, income and opportunity are meager and Cherry feels a family responsibility since her mother died.

‘MOM...MEANT WELL. SHE

JUST DIDN’T KNOW HOW’

Flies swarm. Trash dots the space where a flower bed might otherwise be. A white, plastic chair sits broken on the porch.

For Cherry, public assistance is the norm; watching older siblings cycle in and out of jail is commonplace. Few people in her life have earned high school diplomas or maintain full-time jobs.

She alternates between mind-numbing monotony and hard-fought hustle — lounging in front of the television, then hunting for a roll of toilet paper at the end of the month when money is scarce.

Hers is a life in which painful lessons are learned early: People don’t keep their promises. And dreams don’t always come true.

“I don’t want to be like this for the rest of my life,” Cherry said. “I don’t want to stand on the corner, sellin’ drugs, askin’ people for quarters.”

She added: “I ain’t ashamed of where I’m from. But I wanna dream big.”

Cherry is growing up in a family and neighborhood that epitomize Memphis’ epic struggle with crime and poverty. In Memphis, 36 percent — or 60,000 — children under the age of 18 live below the federal poverty level.

The city’s problems with repeat offenders and crime as a lifestyle are evident in her life.

If Cherry doesn’t make it, she’ll join the tens of thousands of Memphians who have too little education to earn a decent living and for whom a life of crime is a tenable option.

Cherry knows the stakes are high. If she doesn’t graduate from high school, her earning potential will be just under $17,000 a year.

A recent study by the Center for Labor Market Studies at Northeastern University in Boston found high school dropouts ages 16 to 24 were 63 times more likely to get locked up than four-year college graduates.

Basic struggles: Cherry’s sister Destiny helps her try to find the phone number for Memphis Catholic High School after a mentor suggested she set up tours of local private schools. Cherry and Destiny struggled through the Yellow Pages but were unable to find the school’s phone number.

She is already among the 22,495 young people who’ve been through Shelby County Juvenile Court at least once since 2005.

Cherry worries about how easy it would be to slip into street life, selling drugs, panhandling, hustling.

“I guess I’d have to make it the bad way,” she said one afternoon, pondering what life without a diploma might mean. “One day I thought about that and cried.”

The Commercial Appeal followed the teen for six months as she has attempted to change her circumstances, build a foundation for self-sufficiency and plan her dreams. Moments with her were mundane and poignant. As she counted out pennies for a single cigarette. As she ironed her clothes on the living room floor. As she bowed her head at church. As she lay in bed alone, listening to the rain and thinking about her mom.

Cherry’s story speaks to the power of influences in young people’s lives, both good and bad. Which ones will prove strong enough to bend the arc of her life? Only time will tell.

Cherry has lived in a rented house on Davis in Hyde Park since spring 2008. The bedroom ceiling leaks, tattered couches line the living room walls. Knickknacks sit next to an ashtray and a Bible. A printed verse of the Prayer of Jabez hangs on the wall.

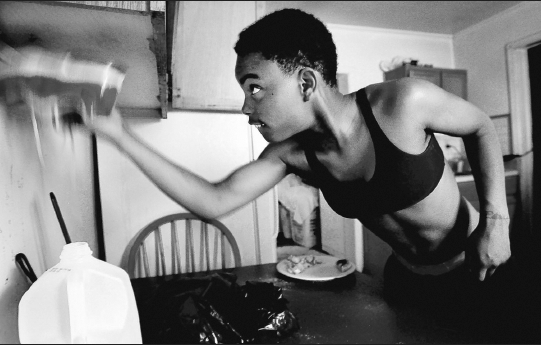

Roaches skitter across the kitchen floor, disappearing behind the stove, and clothes pile up beside the washer..

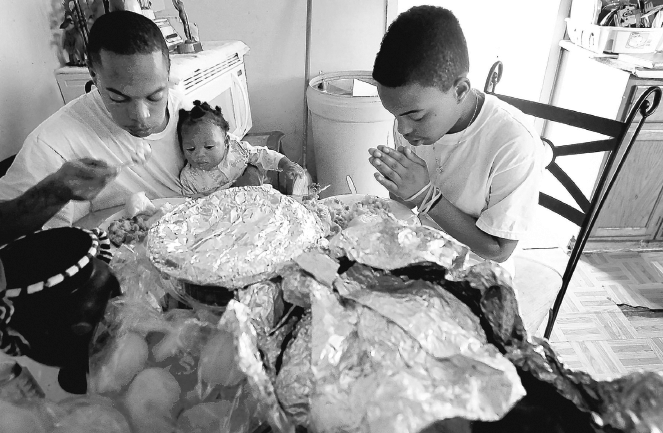

Thanks in order: Cherry prays over Thanksgiving dinner with her sister’s boyfriend, Terrence Rainey, and his son, TA’Derius, 7 months. The meal was provided by Youth Villages counselors. With the help of Youth Villages, Cherry has begun trying to get her life together, control her rebellion and finish school.

Cherry lives with her father, Elton Benson Jr.; her sister, Destiny; her brother, Devonte; and two nephews, Maricus, 18 months, and TA ’Derius, 7 months. Destiny’s boyfriend, Terrence Rainey, 26, also lives there.

Older brothers Elton III and Donti live elsewhere but visit often. So does her older sister Sabrina, a senior at Kingsbury who’s on track to graduate in May.

Cherry’s eldest sister, Tshaica Mallory, 31, lives in Hickory Hill with her husband and three children. Cherry is the second-youngest of her siblings and got her name from being so red when she was little, she said. She has always loved it.

Unwelcome guest: While making pancakes for breakfast Cherry smashes a roach under a kitchen cabinet with her shoe. Roaches often crawl near the stove when food is being prepared.

Cherry wears guy’s clothes and a short haircut, most recently a Mohawk. She likes girls.

At barely 5 feet, her frame belies a toughness that’s apparent as soon as she opens her mouth. She isn’t afraid to fight. As she likes to say: “I’ll beat the brakes off that mug.”

She can be mouthy and belligerent and chafes at authority. One night she got so mad she busted a hole in the bedroom door. She has been suspended at least four times from Douglass High School this school year.

Yet, there’s a less-seen, gentler side — when she cuddles her nephews, writes poetry, when she prays. She has a quirky way of giving her word. For emphasis sometimes, she doesn’t say “I promise.” “On God,” she says instead.

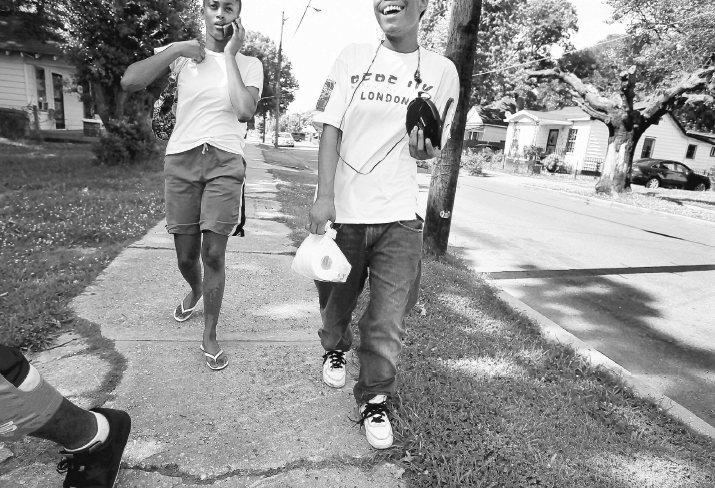

Hustling life’s basics: For most of an afternoon in mid-June, Cherry (right) hustled for a roll of toilet paper. It was too hot to stand outside in front of the corner store to panhandle. A cousin offered her a roll, but her aunt took it back. In the end, her cousin, Precious Adams (left), smuggled it out in her purse and gave it to Cherry at the corner. “I try not to be too much of a needy person,” Cherry said.

“‘I DON’T WANNA DIE YOUNG”

When Cherry wants a change of environment she goes to a friend’s house where she’s given chores and a bedtime. She craves discipline more than she lets on. Like any young person, she wants to be told: I love you. I’m proud of you.

Cherry lives in contradiction. She believes in angels but knows the names of all the junkies at the car wash. Miss Dee Dee. Miss Hollywood. Tony.

She knows parts of the 23rd Psalm by heart but also the price for a single word by the neighborhood tattoo artist: $6.

She can find the bootleg house — where you can buy liquor on Sunday — as easily as the church.

Crime in her neighborhood brushes against every home. Dope dealers blatantly sell on the corner. Gang members flash gang signs to each other. Violent crime has steadily increased there since 2001.

Her siblings have been part of the revolving door of the criminal justice system at 201 Poplar. In early August, the family had a barbecue to welcome home older brother Elton III after he served time on an aggravated assault charge. Cherry’s oldest brother, Travis, isn’t eligible for parole until July 2011. Tennessee Department of Correction records show he has 69 convictions, mostly for crimes of theft or burglary.

A man Cherry calls uncle, the one who lives across the street and tells her to live right, lost his son earlier this year in a fatal stabbing. It wasn’t the first time Cherry thought about getting a gun.

“He’s the same age as me,” she said. “All these kids gettin’ shot. I don’t wanna get shot. I don’t wanna die young. I want to see a lot of stuff in the world. ... My dream place is Puerto Rico or London. To me, it’s calm over there, and I like the accent.”

Mentor support: Joyce Patillo, Cherry’s mentor from the Emmanuel Episcopal Center, took her to tour City University School, a charter school in South Memphis. School had already started, and there were no openings. For a couple of weeks over the summer, “Ms. Joyce” shuttled Cherry to appointments, including one to get her state ID.

DESPITE ESCAPING OLD ’HOOD,

BAD HABITS TEST WILL

Cherry’s three-bedroom house is always full. Friends, neighbors, extended relatives come by to play cards, video games, to spend a couple nights, to smoke a little marijuana. Cherry sometimes shares a bed with as many as three people.

Her oldest sister, Tshaica, helps manage part of the family’s finances, food stamps and Social Security checks. She helps pay the light bill and gives them a little allowance. It’s not much, but she budgets the best she can.

Cherry’s dad gets disability. Destiny recently enrolled in a job-readiness program but has been staying home with her babies. Terrence works as a day laborer a couple of days a week, breaking down old pieces of equipment.

At Cherry’s, there’s no set dinner time, though she can fry a pork chop and scramble an egg. She learned that from her mom.

Terrence cooks now and then, but in the afternoons they run to the corner store for a bag of Flamin’ Hot Lays or Laffy Taffy and a Faygo. “Zoo-zoos and wham-whams,” Cherry calls them.

There are things Cherry has never been taught or learned: how to establish credit or pay bills. How to use a debit card or interview for a job.

To Cherry, a watch is less for telling time and more for showing off her swag, or style. In her world, she waits for somebody to come by.

For a long time she never bothered to learn the spelling of her middle name. “Man, I don’t use it,” she joked.

Cherry may live a tough life and be ill-prepared to make it on her own, but there’s love and laughter in the house she’s growing up in.

Somebody is always rocking one of Destiny’s babies. They share everything from shoes to snacks, and money if they’ve got it. Music often fills the house. They give each other a hard time and are loyal.

Destiny says of Cherry: “I depend on her, but I want her to go to college and not be like these other kids, lost in the world.”

Destiny has her own dreams, too: a good job, a husband, a nice house. Cherry tells her: “You’re going to have one even if I have to buy it for you.”

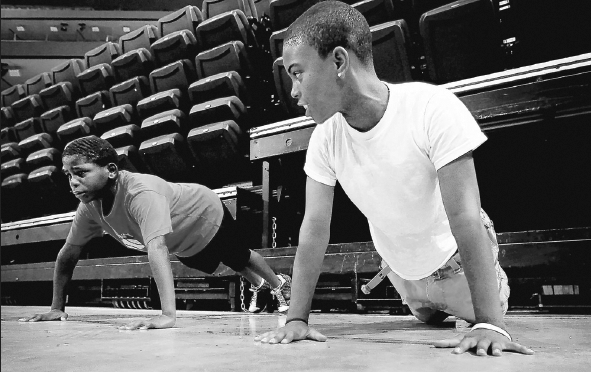

Sympathetic heart: During a visit to FedExForum for a Grizzlies camp, Cherry noticed Lenzell Boyd, 12, crying. He didn’t want to do his punishment push-ups. Cherry dropped to the floor and started doing his punishment, counting: “I love this game! One! I love this game! Two!” After 17, Lenzell joined in for the last eight.

GRATIFICATION DELAYED UNTIL TOMORROW

Doug Imig, a political science professor at the University of Memphis and a research fellow at the Urban Child Institute, says children learn what they live. And for those who don’t see grown-ups going to work or siblings getting high school or college degrees, that life path has little resonance.

“There’s a lot of research about building your pre-frontal cortex, principally in terms of learning how to delay gratification,” he said. “You study now and you stay in school because it leads to a better life.

“But how would you learn that unless you first learn you don’t snack between meals because there is a dinner coming? And you don’t peek at presents before Christmas because then there will be a Christmas morning?

“Well, if there is no Christmas let alone no dinner, how would you ever learn that there’s a connection between delayed gratification and a better outcome?”

Life’s deck was stacked against Cherry Adams on May 30, 1993, the day she was born.

Cherry is too young to have memories of the mother that her older sister Tshaica recalls, the one who read and colored with her kids, cooked dinner and took them Downtown to feed the pigeons.

Crack cocaine changed all that. Their mother, Patricia “Tuttie” Benson, smoked it when she was pregnant with three of her children, including Cherry.

“She loved her kids,” Tshaica said. “... My mom, she meant well. She just didn’t know how.”

When their mom ran off for days, sometimes weeks, at a time when Cherry was an infant, Tshaica and Travis would stay home from school and care for the younger children. They washed their clothes in the tub. Travis panhandled at the Kroger on Cleveland.

“I even remember having to ... cut up Tshirts and stuff just to put on them so they could have Pampers, diapers,” Tshaica said.

After a while someone called the Department of Human Services, and the children were taken into state custody. Their mother kicked the habit and, with drug treatment and parenting classes, regained custody.

Even though her mom was clean, Cherry’s childhood was tough. For years she and her siblings lived in a rented house on Mississippi across from Foote Homes public housing development. The neighborhood has been a hotspot for violent crime for almost a decade, with eight murders in nine years.

At one time, there were as many as 15 people living in their house — plus pets. Patricia Benson never turned anyone away, Tshaica said.

“This guy was living there,” she said. “It got to the point where the lights started getting cut off. He would lie about paying the bills or steal money from her.”

Cherry’s dad remembers the neighborhood this way: “That old place ain’t nothin’ but a bad influence. Dealin’. Everybody got a gun. It might not look like it, but everybody got a gun. And they ain’t scared to use ’em. You got a lot of stupid people in one place, to sum it up.”

Their living conditions and new neighborhood are a significant improvement .

“I can say the bills get paid,” Tshaica said. “They always have food to eat. They get more material things now than they done ever got in they life. And so when I look at that, they gettin’ a better chance in life. It may not be all you want right now, but make the best out of it.”

Voice of experience: Michael Jamerson, who lives across the street from Cherry on Davis, lectures her on staying out of trouble. Just days earlier, Jamerson’s son was fatally stabbed. “She's gotta sit down and think and tell herself to put aside everything besides her education,” Jamerson said.

During Cherry’s early years on Mississippi, a woman who was then- assistant principal at Georgia Avenue Elementary School sparked in Cherry a belief that she could have a better life.

Raychellet Williamson saw a little girl with wild hair who “looked like a boy and talked like a sailor.” She was “a small, little fiery thing. Halle Berry small, but fiery.” At 10, Cherry wanted to fight everybody, her teachers, the boys, “Ms. Williamson.”

Somehow the two bonded. And one year, when somebody brought university flags to hang in the school, Ms. Williamson pointed to one for Rhodes College, her alma mater. She told Cherry she wanted her to go to college.

“She looked at me like, ‘Look at where I live. Are you serious? I hope I survive to 15.’ ” she said. “... But we made an agreement in fifth grade that we were going to get her to go to college.”

Instantly, “Rhodes” became symbolic for a better life. Cherry knows nothing of the school’s prestige or how fast she could drive there from her house. But if anybody asks, she tells them that’s where she’s going.

Soon after Cherry left Georgia Avenue Elementary for middle school, she was officially initiated into the Crips gang. “And you knew it,” Ms. Williamson said. She was hurt but not surprised.

“My brother and some of them were Crips,” Cherry said. “It was like, that looks cool, like fun. And they had a lot of protection.”

She started smoking pot at age 9 and fired a gun for the first time at 12. She sometimes beat up homeless people and took their money.

Hard life, firm resolve: Cherry texts a friend as she and her younger brother Devonte share a place to nap at their house. “I’ve seen all kinds of kids who said they was gonna make it, and they didn’t,” Cherry said. “But I’m gonna make it.”

Cherry has been charged four times as a juvenile, for criminal trespassing, disorderly conduct and resisting official detention. The last time was in 2007. Once, she resisted so violently police used chemical spray to get her into the squad car. The most serious punishment she received was probation.

“We fought the whole neighborhood,” Cherry said. “They started it, so we finished it. They were drunk, full of powder. We fought ’em all.”

Still, some invisible tether pulled Cherry back to Ms. Williamson. Every year on the last day of school she walked or rode her bike to Georgia Avenue Elementary. On those visits, the assistant principal tried to convince Cherry that if she’d direct the same

energy to something positive that she was putting into her street cred, she really could go to Rhodes.

Cherry listened, but not much changed until she was 15. Her mother had been ill for years. She had high blood pressure and had survived a heart attack.

Then late one night in 2008 she told her husband she couldn’t breathe. He called for an ambulance that took her to the hospital. At about 2 a.m., doctors called to say she’d had massive aneurysms. She went into a coma and never woke again.

The family moved from the house on Mississippi to the one on Davis where, for weeks, they took care of her while she lay in a hospital bed. They washed her face, changed her diaper, fed her through a tube. Hospice helped, but they did most of the work themselves.

On June 21, 2008, Cherry sat with her mom before dawn, told her she

loved her and then knelt to pray: “I said, ‘Lord, if my mama has to stay here and be like this just go on ahead and take her.’ I guess it’s best where she is.”

Later that day, while Cherry was out getting a haircut, her mother died. She was 49.

Cherry changed. She started worrying about the future. Who would teach her how to be a grown-up? She stopped picking fights and stayed inside more.

“It made me slow down and think a lot,” she said. “Mama’s not here no more. Nobody’s gonna get me out of juvenile.”

She was scared and told Ms. Williamson once: “Y’all made it. Y’all grown. Y’all know how to pay bills. Am I just gonna catch on to it? Or is somebody gonna teach me?”

The hard way: Cherry Adams, 16, on the verge of tears, calls her dad to tell him she got suspended from school on the first day. “Daddy, I got kicked out of school,” she said. “Daddy, seriously. This time, Daddy, I didn’t do nothin’. I’m not playin’.” Cherry was ultimately suspended nine days for “insubordination/threat against school personnel.”

P R O M I S ES COME CHEAP, DREAMS BIG

In early July, Cherry called Ms. Williamson to tell her she hadn’t been in trouble but needed help to stay on track.

Ms. Williamson called a friend, Rev. Colenzo Hubbard, executive director of the Emmanuel Episcopal Center in the Cleaborn Homes public housing development.

At their first meeting, Father Hubbard agreed to pay the $50 Cherry owed for an ROTC jacket so she could get her report card. She needed to find out if she passed ninth grade. She did.

There was talk of participating in the high school program at the Emmanuel Center and of private school. Cherry needed a smaller environment where she could get close attention from teachers. But she’d have to work harder than she ever had, Father Hubbard said.

“I’m willing to push myself to extraordinary limits to get there,” she told him.

But that exuberance faded in the following days. Anxiety set in as she realized how hard it would be and started to question her ability. She smoked pot to take her mind off the pressure.

Light moments: Cherry jokes with her dad, Elton Benson Jr., at their home in Hyde Park. But at times shewonders who will teach her life skills, such as how to pay bills. “Am I just gonna catch on to it?” she asks.

“I don’t know why I’m afraid of it,” she said then. “I just am. Everything that is goin’ on now is not guaranteed to me. What if everything is goin’ in line

great and, one day, somethin’ happen out of the blue? Somebody passes. I have to move. What if my grades drop? I feel like I’m missin’ one thing. My mama.”

The following week, Father Hubbard and Ms. Williamson gave Cherry a seemingly simple assignment: take tours of local private schools to see which one she liked. It was time to see how serious Cherry was about change.

But the family has no car. Cherry’s dad is disabled and uses a wheelchair. They didn’t have bus fare.

“I call her,” Cherry said of Ms. Williamson. “I text her. I ask if she can help me. She said I have to look it up in the phone book. I don’t know how to look in the phone book and find anything.”

She took the Yellow Pages outside and asked a slew of friends standing in the yard if anybody could help her. Finally, she figured out the number for Memphis Catholic, but it was too late to call.

The next day Cherry listened as her dad asked a secretary about setting up a tour. “If they have any openings, they’ll call me,” he said. “If they call, you can go visit.”

Cherry retreated to the porch and sat alone, sullen: “If they call, they call. If they don’t, they don’t.”

They didn’t.

Cherry’s life experience tells her that everything is in short supply — clothes, food, money, even help itself — so she’s reluctant to ask.

She explained it this way: “When you want something good like a job they say, ‘Nah, I can’t help you do that.’ But then they say, ‘You wanna smoke?’ So you can smoke with me, but you can’t help me apply for a job?”

A week and a half later, Father Hubbard assigned a woman from the Emmanuel Center named Joyce Patillo to mentor Cherry.

For a couple of weeks this summer, “Ms. Joyce” shuttled her to appointments. A tour of City University School, a charter school. But there were no openings. Private school never worked out. To the Social Security office and the DMV for an ID card.

During their long van rides, Cherry and Ms. Joyce talked about choices, negative influences and how hard it is to change. Cherry could tell that this woman, who laughed big and hugged freely, who talked with an attitude but didn’t take any of Cherry’s, spoke from experience. She started to open up.

Everything seemed to be going as planned.

Sibling concern: Tshaica Mallory (left), Cherry’s older, tough-love sister, lets Cherry know that she disapproves of her dressing like a boy. Joyce Patillo (in mirror), Cherry’s mentor from theEmmanuel Center, drove Cherry to Tshaica’s home in Hickory Hill to pick up her birth certificate and health card. Tshaica helps manage the budget at the house where Cherry lives.

The first day of school at Douglass was chaos at Cherry’s house. She was mad that she didn’t have new shoes. She busted a button on her uniform shorts. Ms. Joyce was late picking her up to register. But she was determined to make a good impression.

“I ain’t nervous by a long shot,” she said. “Just ready.”

By Cherry’s account, her first day went well until she asked to use the phone in the office after the last bell. She wanted a ride home because it was too hot to walk. She got mouthy when someone told her no and slammed the phone.

She was suspended for nine days for “insubordination/threat against school personnel.” Cherry cried, swore and defiantly denied she did anything wrong.

Yet she worried she might not get back in school, that Ms. Joyce would abandon her. She became depressed.

But Ms. Joyce didn’t abandon her. She knew Cherry needed the kind of intervention she couldn’t provide. So she called Youth Villages, a nonprofit organization that helps thousands of emotionally and behaviorally troubled children and their families every year.

Counselors intervened on Cherry’s behalf at school and developed a treatment plan at home that includes counseling and independent living lessons.

A counselor meets with her several times a week. It’s a time when Cherry can talk about her mother’s death or

anything else — how to better manage her anger, how to set goals. She writes in a journal and role plays — how to make an appointment, to manage family conflict.

At the moment, Cherry’s goals are to get to school on time consistently and not get in trouble. To that end, her counselor bought her an alarm clock and taught her how to set it. Baby steps, they say, will lead to bigger successes.

“I think the general belief of the community is: How can we help these people?” said Patrick Lawler, CEO for Youth Villages. “They’re really just a lost cause. And most people think that — even in the highest levels of government — that the child welfare system, the juvenile justice system are just a black hole ... that the problem is irreparable.”

But his program’s success rate proves otherwise, he said. That is, two years

after completing the program, 83 percent of participants in 2009 live in stable homes, are either in school or have graduated and have a job, and haven’t had contact with the courts.

Resources for prevention aren’t provided early enough to the small segment of the community with the biggest problems, he said.

“Let’s say there are 5,000 kids in town in Cherry’s set of circumstances,” he said. “Why aren’t there programs like Youth Villages going into 5,000 homes like Cherry’s really trying to get in there and dig?”

He added: “Everybody knows they’re there, but we don’t do anything until they’re brought to the attention of the Department of Children Services or the courts.”

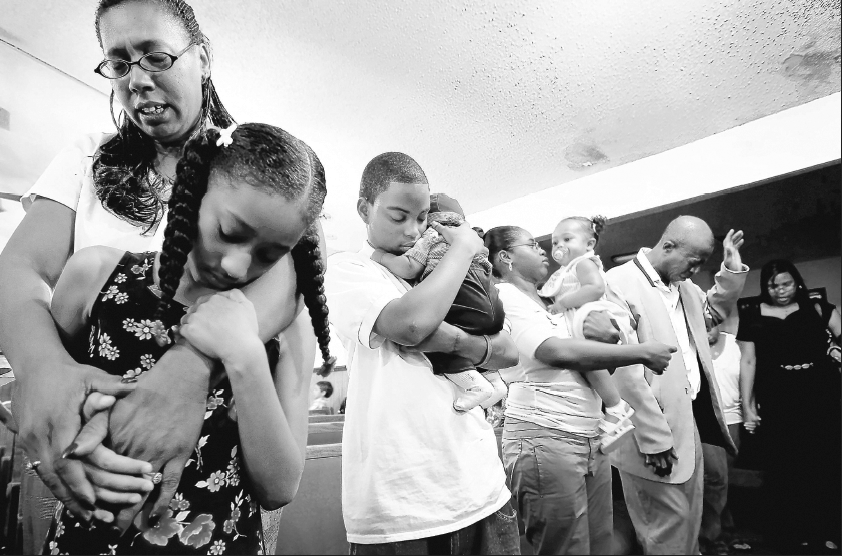

Keeping the faith: Cherry bows her head in prayer while holding nephew TA’Derius at Revelation Christian Center in North Memphis, one of the few times she visited a church this year. “What you look like don’t matter,” pastor Andre Guy-Reed told the congregation as he called Cherry up to the altar. “It’s what you live like.”

SMALL VICTORIES MEASURE SUCCESS

Few dramatic changes have happened in Cherry’s life in the past six months. She still struggles with the same problems, has the same temptations. As of the second week in December, she had an 86 average at vocational school and was failing two classes, algebra and English. But she no longer runs with the Crips.

A job, learning how to budget, opening a savings account — all that will come once Cherry consistently stays in school and keeps her grades up, her counselors say. She has had a taste of what’s to come: a meeting with a credit union branch manager about savings and checking accounts. But opening one is still months away.

Counselors have seen small successes, like when Cherry picked up her test results after a physical on her own initiative. Her attitude has improved. And she reports a decrease in marijuana use. It may take a year to get her where she wants to be, but counselors see promise. They believe in her.

Cherry is smart and intuitive. She can redirect herself and has long-term goals. She can be polite and can handle herself around adults. She’s comfortable with who she is. And she’s resilient .

Cherry has noticed changes in herself too. She’s more respectful of her father. Her anger boils over less.

Yet Cherry’s demeanor swings between bravado and real bravery. She isn’t quite comfortable with the changes in her life. But she’s getting there.

She reflects often on the pact she made with Ms. Williamson in fifth grade about going to college. She thinks about the little gems of wisdom Ms. Joyce offered during their time together. And she continues to meet with her counselors.

It’s becoming easier to make the right choice but not always.

Cherry’s is an experience lived one disappointment, one missed opportunity, one influence — and one tiny thread of hope at a time.

Mentor support: Joyce Patillo, Cherry’s mentor from the Emmanuel Episcopal Center, took her to tour City University School, a charter school in South Memphis. School had already started, and there were no openings. For a couple of weeks over the summer, “Ms. Joyce” shuttled Cherry to appointments, including one to get her state ID.

Basic struggles: Cherry’s sister Destiny helps her try to find the phone number for Memphis Catholic High School after a mentor suggested she set up tours of local private schools. Cherry and Destiny struggled through the Yellow Pages but were unable to find the school’s phone number.

New day, old temptations: Just after 6 a.m., Cherry tucks her hands in her sweater vest to keep warm on a chilly morning as she cuts through several alleys to get to the school bus. The bus stop is at the same corner in Hyde Park where drug dealers ply their trade every night.

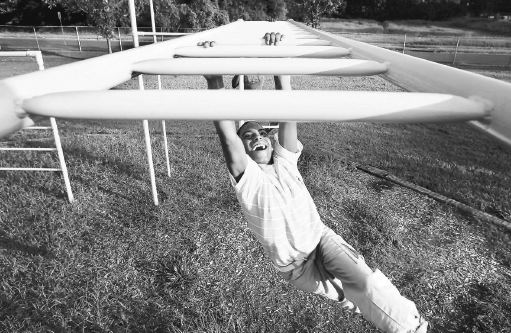

Willpower: On a summer visit to a playground, Cherry struggles to make it all the way across the monkey bars. No matter what struggles Cherry is going through in her life, she believes in herself. Despite a quick temper and a penchant for trouble, the teenager has set her goal on graduating from school and leaving behind the dead-end life she was born into.

Originally published in the Commercial Appeal | All images by Mark Weber