10 seconds of TERROR

Jimmy Cowley shows how he huddled in his pickup as the fury blew out the windows, rolled the truck in mid-air and dropped it at this spot on Mississippi Hwy. 25. The road is a link to U.S. Hwy. 78 and bigger towns such as Tupelo. Cowley marvels at how he survived the tornado. “I covered up, ’cause I thought I was gone,” he said. “... I was burning like fire because that wind and that mud (were) like a sandblaster hitting me.” Brick homes once stood on the now-empty lots along the road.

At 3:47 p.m. on April 27, an EF-5 tornado with wind speeds of more than 200 mph leveled the town of Smithville, Miss., population 942. Seventeen people died in Monroe County, about 130 miles southeast of Memphis. ● The tornado destroyed Town Hall, the police station, the post office, four churches, more than 150 homes and nearly every business. ● Over the past six months, The Commercial Appeal spent time with townspeople, listening as they recounted their 10 seconds of terror, the haunting aftermath of the storm and what some described as the harrowing, heroic, even hallowed day that changed their lives and their small-town way of life. ● These are the stories they shared.

Horror and heroism emerge in Smithville as tornado survivors face lifetime of recovery

Danny Miller was swept up into the whirlwind after helping his wife, Joyce, get in a freezer at Mel’s Diner. The sound, taste and smell of the storm still haunt him.

““I don’t like sleeping too much anymore. ...

I’d rather not sleep than dream about that.””

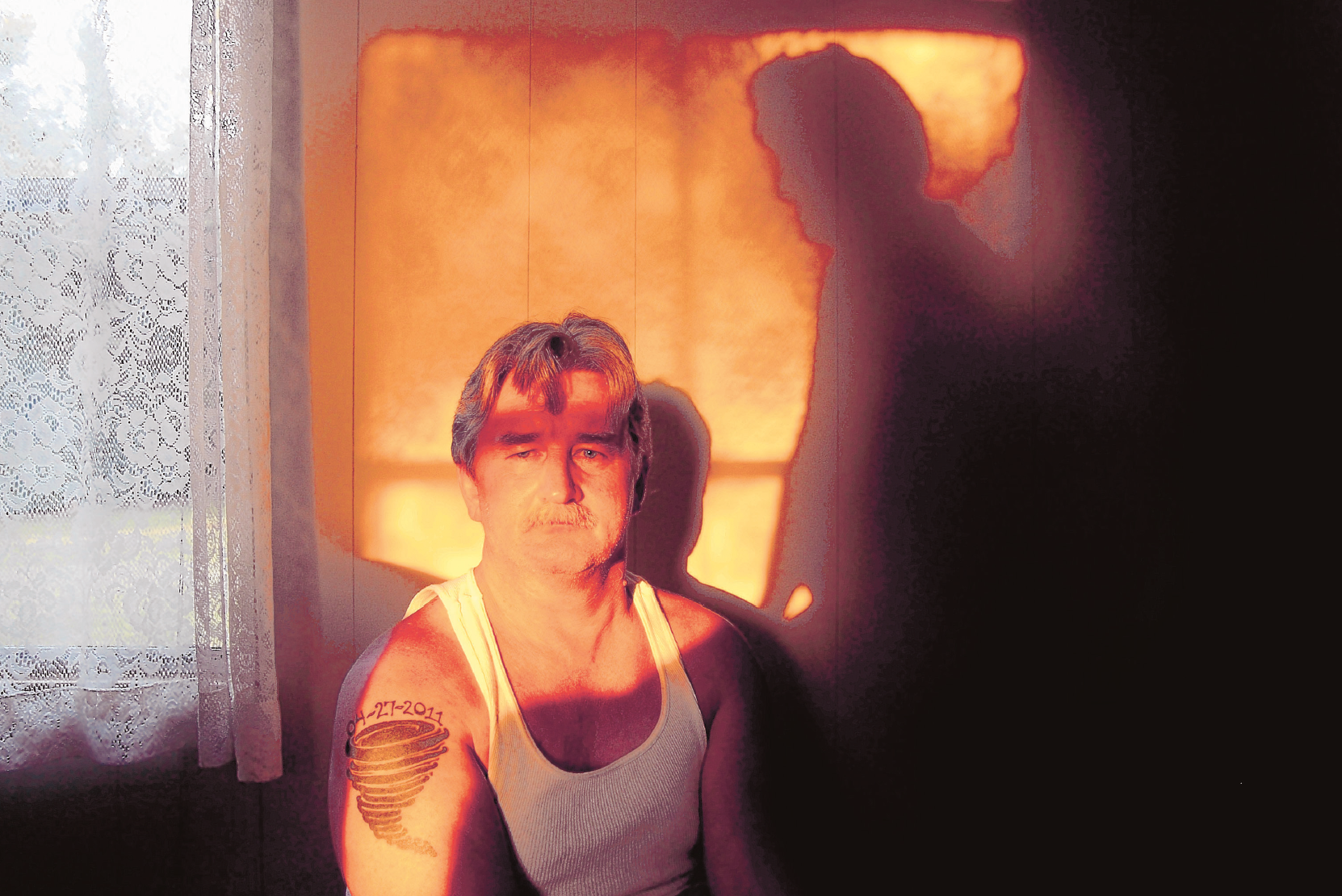

In all the years Jimmy Cowley had known Mikey Phillips, he’d never once seen him speed. But without so much as a country nod, Phillips mashed the gas pedal and flew past his lifelong neighbor up Mississippi Hwy. 25.

Curious, Cowley watched as Phillips disappeared down the two-lane road toward Smithville Town Hall. Cowley never saw the barreling monster in his rearview mirror.

An odd, gray mass, a half-mile wide, covered the Tennessee-Tombigbee Waterway and hastened across the rural road, snapping power lines like the crack of a whip. Sparks burst from the poles like emergency flares, as if to signal the fury to come.

Storm sirens blared all afternoon as ominous storm clouds rolled above 150-year-old pines and flat farmland already planted in rows.

Cowley looked over his shoulder, again and again, thinking the storm would sweep in from the west, the same way showers passed through this map-dot Mississippi town since he was born in 1942.

Then the right window of his Chevy pickup blew out. The storm caught him from behind.

Boom. Every window in the truck exploded.

Cowley hit the brakes and held tight to the wheel to keep the wind from broad-siding his pickup. He made a hard left turn into a driveway, and the back of the truck lifted off the ground.

He was in the whirl of the tornado. Cowley’s pickup slammed the ground on the right side. Mud and grit smacked his face like a sandblaster, swelling his eyes and ears. It felt like his face was on fire. A piece of tin flew through the truck and gashed his head open. Still tucked in his seatbelt, the 69-year-old covered his head as rocks and paneling poked thumb-sized holes through the metal door.

He closed his eyes.

“I’m gone,” he thought.

What Cowley never saw coming had been perfectly framed in the window of Carolyn Boyd’s back door. She watched the rolling black smoke spin across the city-limit line, lift her house off the foundation and twirl it like a child’s pinwheel. The ranch home landed 50 feet across the yard facing the opposite direction. The utility room, carport and breakfast nook sheared off of one side. A recliner knocked her over, shielding her from flying glass.

Moments earlier, Boyd had been on the phone with longtime friend and Bible-study partner, Eva Nell Smith, talking about angels. Boyd had her Bible open to the sixth chapter of Luke; Smith was thumbing through Revelation.

“Ms. Eva Nell, I don’t feel right about things today,” Boyd said. “I think something bad is gon’ happen.”

Not long after the two hung up, Smith looked out the window and saw her car and half the garage flying toward the living room where she was standing. She grabbed a couch cushion to shield her head, but something that felt like two hands gently pushed her to the end of the hall. She was alone, she knew. Her husband had been dead 10 years. But there was that gentle push again.

“Time stood still,” Smithville Police Chief Darwin Hathcock said about looking at the devastated town immediately after the storm.

It was as if someone punched a button to raise the roof off the house. It never broke apart; it simply flew away. She could see the sky —red, yellow and white. She reached for the linen closet, but there was no linen closet. Three windows, a bed and a door flew at her. She turned her back, and those two hands pushed her to the other bedroom. She watched as the wind sucked bricks out from under two windows. Then the hands shoved her through the windows to the ground outside near her rosebush.

Smith’s Bible followed her. The pages were grimy and the back torn off, but the bookmark still held her place in Revelation.

A few blocks east, Mona Young was outside with her son in the driveway when she saw the massive wall speeding toward them. She kicked the car door open to get out, the force of the wind nearly pinning her in the driver’s seat. She and 13-year-old Fisher barely made it inside. They sprinted to the bathroom.

“We ’re gonna die!” Fisher screamed.

Just as Young lay on top of her son in the bathtub the tornado overtook the house. The wind was so strong it lifted her off the ground. They heard trees snap and nails pry from house’s frame. The smell of fresh-cut timber and earth filled their nostrils.

“God spare us,” was the last thing Mona Young said.

Over at Mel’s Diner, Paul Estis had just sat down with his family to eat before they headed to Wednesday services at Trace Road Baptist Church when owner Bobby Edwards called with a grim warning: turn off the gas and get in the cooler.

At first, lightning, hail and thunder were strangely absent from the sky. A peculiar sound — like a jet fan with trash stuck in it — pierced the still air.

Eva Nell Smith felt a force guiding her to safety as the tornado ripped her house apart around her. “Two hands just pushed me into the other bedroom,” she said.

“I know there is a God because I felt his hands on me, and he saved me.”

Joyce and Danny Miller, who lived in a rental house next door, made it inside just before the tornado tore the diner apart. Joyce got in the freezer, but it was too late for Danny.

With a dozen people crammed inside the cooler, Paul Estis’ eldest daughter, Cara, clung to his leg as he gripped the door’s bar handle to keep it from swinging open. The enormous pressure caused the latch to slip, popping it ajar.

The cooler was vibrating as Estis prayed: “Thank God we’re all together. ”

Outside the cooler, Danny Miller was already a few feet off the ground.

“Oh God,” he screamed. Then the wind took his breath away.

Iron bars twisted above him. He could taste the fiberglass coming out of the walls.

The wind flipped him over and laid him on the under-shelf of a metal prep table as if it had tucked him in bed on the bottom bunk. He watched through a hole in the ceiling as the storm inhaled nearly everything in its path. It was the worst sound Danny Miller had ever heard, a high-pitched scream, the scratching and squealing of a demon trying to spirit him away.

By that time, Mikey Phillips had made it to Town Hall, a good half a mile from where he’d whizzed by Jimmy Cowley. He’d hit 85 mph for sure, maybe 90. Still, the storm was too fast. He couldn’t outrun it.

Phillips got out of his truck, thinking he’d crawl under a heavy desk in Town Hall. But Mayor Gregg Kennedy had locked the front door. As the storm passed, Phillips was stuck in the foyer. The wind rolled back the roof like the pull-key on a sardine can.

The outside brick wall and two picture windows collapsed on Phillips. Blood dripped from his arm, staining his white T-shirt red.

Next door, the surveillance cameras mounted at the police station captured the storm’s power. At first it seemed as if the camera affixed to the garage zoomed in for a closer look until it captured grainy debris. The camera had been sucked into the whirlwind.

The tornado was so large Police Chief Darwin Hathcock was certain it would engulf the entire town. “There’s no way we’re gonna survive , ” he thought. “Nobody is gonna survive this storm.”

Serenity washed over him. He was at peace. He’d given up.

Michele Wardlaw emerged from her brother’s house into a sensory void. With the massive tornado a block and a half away, she heard no sound and felt as if everything was moving in slow motion.

“It was like our heads were going to explode and our ears were going to burst.”

When Michele Wardlaw stepped on the front porch of her brother’s Elm Street home, the tornado was a block and a half away. It was so wide and so close it looked like a breathing mammoth of dust without beginning or end. It snatched the roof off the Piggly Wiggly and tore the awning from the police department, flinging it into a house.

With her grandmother on one arm and her brother, who’d been injured in a fire, on the other, Wardlaw ran toward the nearest storm shelter.

Her mom and children ran ahead but couldn’t get the door open. She could see their mouths moving: “Come on, Mom! Come on, Mom!” But she heard no sound. It was as if she’d abruptly gone deaf.

Wardlaw raced to the storm cellar, flung the doors open and hurried back for her grandmother. Dirt and glass pelted her skin. But what she saw left her mesmerized.

Common sense told her to run. But she couldn’t take her eyes off the white dots surging in and out of a massive black wave, like a violent, floating tide that swept shells of cars and houses in and carried them back out again. Just then a white car flew overhead.

Time seemed to loiter.

“I can’t move,” Wardlaw thought. “I’ve got to see this. This is just unbelievable . ”

Wardlaw grabbed her grandmother under her arms and walked backward toward the storm shelter. The tornado lifted her grandmother’s feet off the ground, twisted them both and cast them into the stairwell of the storm cellar.

Folks from the local trailer park pulled into Smithville Baptist Church’s parking lot, looking for shelter. Pastor Wes White invited them into the old church nursery. Trepidation swelled with every spin of the storm siren. But White and youth pastor Todd Summerford weren’t quite ready to go inside. They watched the sky grow darker. Limbs and leaves began to fall out of the sky. They stayed long enough to snap a few pictures with their cellphone cameras.

In an instant the roar was upon them. White grabbed a door frame and a support pole and huddled with the group. The pressure was profound — as if a pilot had made a sharp takeoff and never leveled out. The preacher didn’t hear the things he saw.

But White quickly forgot his ears as the room was engulfed. It was as if a phantom hand assaulted them with rain, mud and insulation. Ceiling tiles disappeared one by one. White could see the fellowship hall disintegrating. Toys and Bible study materials whirred around the room as if someone had set a colossal food processor to chop.

The only two windows left intact were directly in front of them. Surely, the preacher thought, it was the hand of God.

Barbara and Stephen Umfress were both severely injured. Barbara’s scars are finally healing at home after a brain injury put her in a coma for 18 days.

“All I had in my mind was my wife ain’t gonna make it. ... I’ve killed over 100 deer in my life. ... I’ve seen a lot of things die. ... I knew she was on the edge of it.”

Patti Parker left her office in Amory, Miss., the next town over, in the middle of the storm, thinking she’d rush ahead of it. She got as far as Pecan Road on Mississippi Hwy. 25 when she saw the tornado on the ground. It was in front of her. She’d missed it by seconds but watched from its wake as the tornado razed the town. She pulled over and sprinted to her house in heels.

A ghostly quiet settled over the one square mile that comprises Smithville city limits. Natural gas spewed from broken meters. The ground was moist like sponge cake. The abject stillness left Parker feeling as if she were in her own silent movie. All she could hear were her feet hitting the pavement and a panting she realized was her own.

Parker ran past a man who’d crawled out a broken window of what was left of his pickup. Blood covered his face, his left ear packed with mud. He looked dazed but could talk. It was Jimmy Cowley.

“Mr. Jimmy?” she asked. “Are you OK?”

Her face held a desperate expression. She needed to find her family. He waved her on.

The landscape left Parker horror-struck.

Nothing looked familiar. None of the usual landmarks stood. Victory Baptist Church was gone. Houses that had marked the entrance to Smithville from Amory for decades had simply vanished. Bark was stripped from trees like skinned animals. What people had worked a lifetime to build — and in some cases generations — was gone.

For an instant people across Smithville wondered: Am I the only one who survived?

Parker ran on, jumping debris and power lines until she saw enough blond-colored brick to recognize a neighbor’s home. She wasn’t yet to her own when she began screaming for her husband: “Randy! Randy!” As she made her way up the driveway, Parker’s husband, son and daughter walked out of what was left of the front door. They were alive. She scooped them in her arms.

“Thank you, Jesus,” she said. Dazed, townspeople took several minutes to register what happened. Some staggered, disoriented. Others became frantic. Then screams came from every direction.

“Have you seen Daddy?” “I can’t find Mama.”

“Help us. My daughter is trapped."

What they saw before them made no sense. Every house, every business and barn, every flower bed, every piece of farm equipment — all of it was torn to pieces or simply gone. An 18-wheeler had blown off the road, smashed like a tin can. Power lines draped rooftops and roads. Trees had been lifted from the ground by their roots. The wind rippled a stretch of blacktop as if had been a roll of carpet. All of Smithville looked like a landfill piled with garbage.

Police officers, firefighters and volunteers from across northeast Mississippi headed to Smithville, but until they arrived, people were on their own.

The dead lay naked in fields. The ferocious winds had ripped the clothes from their bodies. People had broken bones, bleeding limbs and split skulls. Some had been impaled.

It began to rain.

Dr. James Monroe and his staff stumbled out of the medical clinic where they’d been seeing patients all afternoon. Their surgery suite was in shambles. They had no supplies.

“Help!” Monroe heard someone scream from across the road.

Dr. James Monroe, with his clinic’s supplies blown all over Smithville, felt helpless but saved lives in the bloody aftermath of the storm. A door used as an improvisational stretcher has been framed as a reminder.

“It’s just the hand of God reaching out ... there was some peace about it. In all the conflict, in all the disarray, there was still some peace.”

Six people had stuffed themselves into a bathroom but were blown to the front yard of the home that was no longer there. The only thing left on the foundation was a dresser and a bed with sheets still on it.

Steve Umfress was on all fours on the soaked ground. The sound of the tornado reminded him of a buzz saw and then a thousand pigs squealing. A board came through the bathroom wall like a bullet shot from a gun.

The last thing he remembered before being knocked out was the wall collapsing.

Umfress couldn’t see out of his left eye. Something was obstructing his view — his own forehead. A horseshoe-shaped flap of skin had torn away from his skull and hung over his left eye. He held it in place with his hand, worried he might bleed out.

Everybody else seemed all right except his wife of nine weeks, Barbara, who lay in front of him. Umfress was no doctor, but he’d killed enough wild game to know what death looks like. Her breath was more a gurgle, and her eye was rolling back in her head. Umfress knew if someone didn’t reach her soon she’d die.

Those who weathered the storm in cellars emerged to find that in 10 seconds, the town was gone. Once-familiar Smithville scenes were unrecognizable. Eyewitnesses saw cars flying and homes exploding as winds destroyed more than 150 homes, the grocery, gas station, post office, police station, clinic, restaurants, churches and Town Hall.

Dr. Monroe ran to her first. She was lying in the muddy grass, twisted. She was seizing. He thought she might die in the next breath. Monroe yelled to a nurse to search the clinic for a plastic airway. She brought the only one she could find. He placed it.

Helpless, Monroe moved on. Without equipment there was nothing more he could do.

Maybe 100 feet away the country doctor found a man with a broken leg. The nurse asked if anybody was in the pile of rubble next to him.

“Well, there was somebody, but he’s gone,” the man said.

Gone where? They wanted to know. He pointed to the sky.

Michele Wardlaw, who was flung into the storm cellar by the tornado, opened its doors and walked out. She realized her step-grandmother, Maxine Chism, hadn’t made it to a shelter. She found her — alive —lying beside a ditch near the railroad tracks. Wardlaw prayed with her until she heard two children on Dunlap Street. She ran to them.

Emily Jo and Josh Pearson suffered skull fractures when the tornado picked them up. Their aunt, Carla Jones, who got on top of the children to try to hold them down, was killed. Josh remembers flying in the air.

“When I got sucked up from the tornado, it ripped my house apart. I went up in the air. I didn’t know where I was going.”

Josh and Emily Jo Pearson, ages 8 and 4, sat alone on a slab. Wardlaw held them close. She kept the stocky boy talking, but the blond-haired, green-eyed girl only stared. She wouldn’t speak.

Wardlaw dialed 911. EMTs were on their way, but roads were blocked. It would be a while before anyone could reach them.

Turning her head up to the woman who held her, Emily Jo asked: “Am I gonna die?”

Then she passed out in Wardlaw’s arms.

Dan and Peggy Chism’s storm shelter saved 10 people, ranging in age from 1 to 91, as winds more than 200 mph took their home. When they emerged, their former neighborhood was gone. Dan said life will never be the same.

Volunteers plucked doors out of the rubble to use as stretchers to carry people as far as they could muster toward the highway. Wardlaw and two other women carried the children on plywood and then went back for her step-grandmother. They put Chism in the rear of a pickup and went back searching for survivors.

Vickie Clingan was trapped under four or five feet of debris. Her house had collapsed around her. No matter how hard she tried, Clingan couldn’t wiggle free. She called 911 but couldn’t get through. She called her son, her husband, but only got voicemail.

A few seconds later, Clingan heard screaming above. If she could hear people, she thought, maybe they could hear her.

“Could someone please come help me?” she yelled. “I’m OK, but I just can’t get out.”

A voice came through. Some men asked Clingan where she was. She poked a piece of door frame through a hole so they could see the spot. But the men worried aloud that if they started digging, the fragile debris might crush her to death.

Clingan realized she might never get out.

“God, if this is my time, I’m ready, ” she prayed. “But please take me quick.”

Then she heard another man’s voice. It was Terry Hall. He’d been at home in Hatley, Miss., a 10-minute drive from Smithville, when the storm came through but got a call from his wife, Dianne, who works at the medical clinic. She told him to come to Smithville, knowing he could help if people were trapped. He’d worked in construction all his life.

“You know, guys, I believe I can get her out,” he said.

Clingan heard him slinging debris. Little by little, she felt the pressure on her body ease. She shimmied enough that the men above could lift her out. Clingan looked up, expecting a hand. What she saw was a hook. She was overwhelmed but grabbed the prosthesis to steady herself as others lifted her out.

“A man with one hand is who dug me out,” Clingan thought.

She never saw his face.

Terry Hall dug Vickie Clingan out of a suffocating pile of debris after her house collapsed around her.

“The only tools I had was the one good hand that I’ve got, and the hook ... I just went in and done what I had to do.”

Still in her pajama pants and barefoot, Clingan embraced her husband, John, who’d made his way home by then. She asked about her mother, Lucille Parker, who lived next door. Men standing behind Clingan shook their heads.

Dr. Monroe said softly: “Ms. Clingan, I’m sorry. But your mama’s gone.”

Gone, she thought. She couldn’t yet comprehend what had taken place.

Kellie Estis hugs close friend Carol Leech on Elm Street while Tonya Wright stands close by. Kellie’s parents, Roy “Peanut” and Ruth Estis, were in each others’ arms when the storm lifted Ruth into the sky. Roy died the following day.

Back at Mel’s Diner, Paul Estis stepped out of the cooler. Danny Miller’s eyes were as wild as his hair. He ran out to catch the last glimpse of the tornado before it disappeared from town. In his hand was an unopened 20-ounce bottle of Coke. He didn’t remember leaving the house with it.

Estis gathered them for prayer and then looked toward his parents’ house on Elm Street. He told his wife he had to go.

“He said, ‘Son, I was holding her in my arms and she just went up and I couldn’t hold on.’ I looked at him and said, ‘Daddy, I love you. But I think Mama’s gone.’”

Halfway down that block, Estis spotted his Aunt Peggy Chism, whose home was across the street from his parents’. Her house was gone; so was theirs.

Roy “Peanut ” Estis sent his 8-year-old grandson, Gable, across the street to the Chisms’ storm cellar but stayed behind with his beloved Ruth. She was on oxygen and too frail to make it across the street. And after nearly 43 years of marriage, he wouldn’t leave her. He held her in the hallway as they braced for the storm.

When Paul Estis found his father, he was propped up in a straight-back chair on top of what was left of the house.

“George! George!” Peanut hollered out, a pet name he’d called his wife for years.

“George, where you at?”

Peanut’s face was bruised. He had a hole in his stomach from a piece of glass. Paul looked for his mother as his father spoke.

“Son, I was holding her in my arms, and she just went up, and I couldn’t hold on,” he said.

“Daddy, I love you,” he told him. “But I think Mama’s gone.”

By then, Paul’s sister Shellie Brown had arrived with her two children. Peanut was looking out over the rubble toward the cemetery when she bent down to talk to him.

“Mama’s missing,” he said.

“I know Mama’s missing,” she told him. “Are you OK?”

“I’m fixin’ to go,” Peanut said, his eyes rolling back in his head.

Brown shook him. “Daddy, you can’t go. You can’t go. We got to find Mama.”

It took hours before someone found Ruth Estis on the soft ground, eyes closed, dead. Someone on a four-wheeler carried Peanut to the highway.

Paul and Shellie had no idea if their father would live until morning.

Kellie Estis, Shellie Brown and Paul Estis are three of four siblings who lost their parents, Roy “Peanut” and Ruth Estis. A flag in the field marks the place where Ruth’s body was found. “I didn’t want to find my mama, but ... you want to know what happened,” Paul said.

When Mayor Gregg Kennedy and two clerks crawled from beneath the board table at Town Hall, they could see the sky.

Mikey Phillips, the mayor’s hunting buddy who’d been stuck in the foyer, was bloody from head to toe. Kennedy helped him hitchhike through the back roads to the hospital.

In an instant this small-town mayor’s duties went from dogs and ditches to one of the state’s worst natural disasters since Hurricane Katrina. Kennedy directed the water superintendent to push debris with a back hoe. Roads had to be cleared if ambulances had a prayer of making it in.

Few city structures were still intact. A small metal shed used to store parts for the water department was the only place that had a door they could secure. It became the makeshift morgue.

Four-wheelers backed up to the door and dropped off bodies wrapped in quilts, bed sheets, plastic and carpet as a volunteer firefighter stood guard at the door. People had been sucked from their homes and dragged through debris. Mud, insulation and glass stuck to their bodies like glue.

Kennedy ran across the street to what was left of the Piggly Wiggly and asked for gallon jugs of distilled water. He took cotton rags from the maintenance shop and dabbed the faces of the dead. He washed four before the Lee County coroner arrived to take over but didn’t recognize a single person, though he’d known them for years and had spoken to one not two hours before.

Ann Seales, one of the Town Hall clerks, left the mayor to deal with the rescue effort. She had to find her husband of 52 years, Jackie. She set out walking up Mississippi Hwy. 25.

The people she passed were delirious with worry: “Have you seen my child?” “Have you seen my dog? “Have you seen my sister?”

“No, I haven’t seen anyone,” she told them.

About a block down the road, Seales looked up. Her husband was coming toward her. They clung to each other.

“Thank the Lord,” she cried. “Yo u ’re alive. You’re OK.”

“The house … ” he said.

“That don’t matter,” she told him. “We’ve got each other.”

ackie and Ann Seales, married 52 years, were on different ends of Smithville when the tornado passed. They searched for each other on the debris-strewn highway through town. When she saw him, Ann said, “Thank the Lord.”

For the next six hours Pastor White gave comfort. He took a mental inventory of who was safe and who’d been taken. Caleb Reeder, Hal Morgan, Marcel Medley —alive. Mildred Elam, Elvin Ray Patterson, Laverne Patterson — all gone.

National Guardsmen formed a wall to hold back family members as body bags were taken away. With each pass they wondered: Is this the one I love?

A profound clarity about the frailty of life washed over Pastor White. He thought about the Psalmist David: Our lives are but a vapor. What is man that God is mindful of him?

Long after the sun set over Smithville, residents made their way to hospitals and homes of friends and relatives, to hotels if they could find them. Aunt Peggy Chism went to Wal-Mart with her husband, Dan. He had to buy an entire wardrobe from underclothes up.

A doctor in Tupelo sewed up Jimmy Cowley’s head. There was no electricity or water at his house. When he and his wife turned out the lantern to sleep, there in the dark, Cowley realized he hadn’t yet thanked the good Lord for saving his life. He said his prayers.

But Cowley did not rest. All through the night the tornado was with him. He relived the nightmare again and again.

The crisp American flags that lined Mississippi Hwy. 25 in late April no longer stand six months after the storm. People have settled into new routines. Some bought houses; others have begun to build. The dead have been buried.

In some ways, the town’s character remains. Folks farm by hobby if not by trade. They can vegetables and hunt. Lady Liberty and the King James are their touchstones.

They take pride in the same bygone glories, not of fortune, but by some measure, of fame: the 1993 and ’98 state football championships; and Rod Brasfield, a hometown hero who performed in the ’50s on the Grand Ole Opry.

But some things will never be the same. The historic tornado that changed the landscape of Smithville also reshaped lives.

The children Michele Wardlaw held on Dunlap Street had skull fractures and puncture wounds but survived. Their aunt, Carla Jones, who was babysitting them, did not. Her son Austin Jones, who was also at the house, was flung into a field behind the house. After three days in a Memphis hospital, he learned his mother’s fate. Now he sits at her grave, at the impressionable age of 17, and talks about how life has changed.

Maxine Chism, who was found alive near the railroad tracks, lived for three weeks but died of her injuries. She was buried in Smithville.

Paul Estis and his siblings made it to the hospital in time to see their father, Roy “Peanut ” Estis, before he died. Paul ’s sister, Shellie Brown, still feels their parents’ presence on the land even though the property is empty. The profound love and devotion that bound their parents in the hallway is something they’ll tell their children of again and again.

Mona and Fisher Young survived. The teenager believes God has a purpose for him.

The horseshoe-shaped scar on Steve Umfress’ forehead is a reminder of the storm each time he looks in the mirror.

His wife, Barbara, was in a coma for 18 days with a brain injury. Her recovery has been slow but remarkable. She went from not knowing her own birthday to reminding her husband that it’s time to take her medicine. She’ll be well enough by Christmas to take that honeymoon trip they never got.

Peggy and Dan Chism have each other, but belongings collected over 52 years of marriage left them. Though they’re retired, they have to start from scratch.

Vickie Clingan, who was trapped in the collapsed house, spoke by phone to Terry Hall, the man with one hand who rescued her, and thanked him for his kindness. She moved away from Smithville, the memories too painful to rebuild.

For Jimmy Cowley, life has returned to normal. Most mornings he rides a tractor across his hay fields. He no longer dreams about the storm. But the memory of the tornado is with him most days.

He wonders how he survived the whirlwind in a pickup truck when so many died inside sturdy, brick houses: Celia Fay Jackson not 100 feet to his right in her home just off the highway. And Elvin Ray and Laverne Patterson in their home to his left.

He’d had coffee that morning with Elvin Ray at Phil’s Place, the restaurant where retirees sat up front and solved the world’s problems.

The restaurant is gone. And so is his friend.

All across Smithville, residents find meaning in the smallest circumstances. They say with candor how proud they are to see each other. They talk more of God. And grace.

Many grapple with universal questions that often arise after tragedy.

Why did I survive?

What is my purpose?

Some still talk of what seemed like suspended time that day. For others, their dreams are still in that space.

Austin Jones lies near the grave of his mother, Carla Jones. He talks to her there.

“She knew that I was scared because the weather was getting bad and I had never seen anything like the way the clouds were forming. She always knew that her smile could always ... make me feel better — and she smiled the biggest smile I’d ever seen her smile.”

For many, the thought of leaving Smithville is preposterous, a conviction as clear as the familiar whistle of the Andy Griffith theme song on the

mayor ’s cellphone. Smithville is their Mayberry, a place where they can find anything they need and everyone they love.

The tornado simply bound them more firmly to each other and their small-town way of life. It also gave them another shared story, one they’ll tell for years to come.

Like the time a tornado swept Jimmy Cowley right off the highway in his Chevy. And how he took a ruler all the way to Amory, Miss., to measure rearview mirrors before he bought a new truck.

Though it didn’t happen that way, they’ll tell Cowley’s gussied-up version: How he picked a Ford because it had the biggest mirror even though that Chevy saved his tail.

They’ll swear it was because he had no intention of ever letting another tornado slip up behind him again.

Originally published in the Commercial Appeal | All images by Alan Spearman